In a nutshell . . . .

This page introduces you to the Watching-assessment-recognition idea of the Practice Competence & Excellence (PCE) dimension. This idea is the first of the four ideas that make up the PCE critical circle of clinical responsibility. It will be stressed that this three-fold idea is absolutely VITAL to PATIENT SAFETY.

As you know we usually use the idea of assessment to cover everything we do to identify and monitor patients' condition. But, in Careful Nursing we aim to identify and recognise in depth everything we do as nurses.

You'll read about the historical background of nurses' 24/7 watching of patients, a responsibility which in the past was considered vital but is currently easily be taken for granted. Even though you know much about assessment, you'll be encouraged to think about the differences between a nursing assessment and a medical assessment. Then you'll read about why watching and assessment alone are not enough and why we must also highlight the importance of recognising what we see when we watch and assess patients. You'll find illustrations and examples of how watching-assessment-recognition work together.

You'll also learn more about identifying collaborative problems and the importance of watching-assessment-recognition in collaborative practice.

Introduction

Watching-assessment-recognition is the third Practice Competence and Excellence (PCE) concept and the first of the four concepts that form the Careful Nursing critical circle of clinical responsibility. The components of this three-fold concept are both distinctive and folded into one another. Before continuing, please take a minute to review the two figures on the PCE introduction page above to remind yourself how this concept relates to the other seven PCE concepts (first Figure) and where it fits in the critical circle of clinical responsibility (second Figure).

Watching-assessment-recognition has been defined as:

a composite of nurses constant visual, perceptive and experiential attentiveness to patients and alertness to their bio-physical/psycho-spiritual condition and needs in order to recognize as immediately as possible any changes in their conditions or their levels of responsiveness to medical treatments, collaborative problems and nursing interventions (Meehan 2014, p.11).

Watching-assessment-recognition has two important purposes:

1. The safety of the people we care for, especially in acute care settings. This concept lies at the root of one of the nursing profession's primary and definitive responsibilities; the protection of sick, injured and vulnerable people from harm.

Watching-assessment-recognition is closely related to the following concept, clinical reasoning and decision-making, and serves as a 'first alert' or 'early warning' of potential or actual physiological instability in patients, addressed in Careful Nursing using the Carpenito (2017) concept of collaborative problems.

Failure of nurses to carry out this collaborative responsibility well can lead to untreated deterioration of patients' physiological status and "failure to rescue" patients from near death or actual death (Garvey, 2015, p. 145).

2. As the first step in the nursing process, watching-assessment-recognition forms the basis for clinical reasoning and decision-making related to identification of nursing diagnoses, identification of nursing outcomes and their measurement, and identification of nursing interventions, all as they relate to both immediate patient care planning and discharge or long-term care planning.

If watching-assessment-recognition together with clinical reasoning and decision-making are not performed well nurses lose control over the nursing process and control over their practice (Herdman & Kamitsuru, 2018).

This purpose of watching-assessment-recognition leads to the fourth concept of the PCE critical circle of clinical responsibility, diagnoses-outcomes-interventions.

Collaborative problems

"Collaborative problems are specifically defined as physiological problems that are at risk to occur or have occurred that require both medicine and nursing interventions to treat" (Carpenito, 2017, p. 20); "nurses monitor to detect onset or changes in status" of such physiological problems (p.21).

Collaborative problems concern patients' potential, or risk, for becoming physiologically unstable or actually being physiologically unstable; they are threats to patients' safety. It seems wise to always link the term "collaborative problem" to the term "physiologically unstable" because this term can serve as a more direct alert to the possible physiological threat to patients' recovery or their life.

Carpenito (2017) explains that not all physiological problems, or types of physiological instability, are collaborative problems. Potential/at risk, or actual physiological problems can range in seriousness from not being immediately threatening, for example impaired skin integrity, to being immediately and critically threatening, for example increased intracranial pressure.

Physiological problems, or types of physiological instability, that are not potentially or actually immediately life-threatening and which nurses detect and can prevent and treat independently are not collaborative problems but nursing diagnoses, for example impaired skin integrity or deficient fluid volume.

But physiological problems, or types of physiological instability, that are potentially or actually immediately threatening to patients' recovery or their life, and which nurses detect but cannot prevent and treat independently are collaborative problems; nurses engage in watching-assessment-recognition 24/7 to detect onset or further development of actual collaborative problems, for example bleeding or cardiac arrhythmias, and collaborate with medicine in treating them.

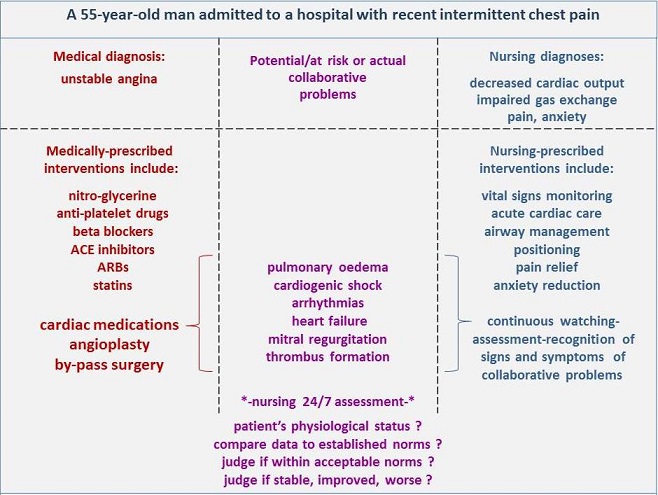

"Nurses manage collaborative problems using physician-prescribed and nursing-prescribed interventions to minimize the complications of the events" (Carpenito, 3017, p. 21), for example, as illustrated in the following Figure:

Or, for example, a patient who has suffered a serious head injury will have the potential/at risk or actual collaborative problem of increased intracranial pressure. If the patient is at-risk for increased intracranial pressure nurses will watch for, assess, and recognise the earliest possible indicators of increasing intracranial pressure. If the patient actually has increased intracranial pressure nurses will watch, assess and recognise movement in level of intracranial pressure, especially any increases in pressure.

Physician-prescribed interventions may include medication or surgery. Nurses will watch for, assess and recognise the meaning of vital signs and other physiological indicators continuously. A related nursing diagnosis might be anxiety related to threat to health status, and nursing-prescribed interventions may include active listening or progressive muscle relaxation.

Watching-assessment-recognition of patients to detect the earliest possible indications of collaborative problems, and their collaboration with medicine in treating these problems, represents nursing's closest possible collaboration with medicine. In effect, there is a critically important overlap in nursing and medical responsibility for patient care; this collaboration may also include other disciplines, such as respiratory therapy.

The following Figure adapted from Carpenito (2017) illustrates collaborative problems at this important overlap of nursing and medical responsibility:

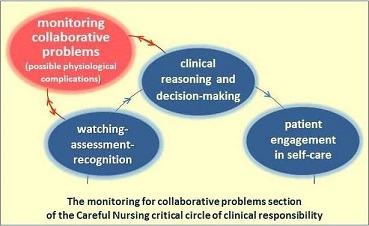

The threat of physiological problems/physiological instability to hospitalised patients' safety and recovery highlights particularly the vital importance of the PCE watching-assessment-recognition concept in the detection of collaborative problems; detection is a synonym for recognition. Watching-assessment-recognition in conjunction with clinical reasoning and decision making are integral to the Careful Nursing critical circle of clinical responsibility (see PCE Introduction page, second figure) and are critical to keeping patients safe.

The Figure below shows the collaborative problem section of the critical circle of clinical responsibility Figure. Patient engagement in self-care is included because patients are always engaged in their care to the extent that they are able and wish to do so

Nurses responsibility for monitoring patients for possible collaborative problems is a primary reason for nurses' 24/7 relationship with patients and directly relates to the vital importance of adequate professional nurse staffing levels in hospitals (Aitken et. al, 2014).

Carpenito (2017) provides a comprehensive overview and focused discussion of collaborative problems in relation to nursing and medical diagnoses (pp. 21-27; pp. 32-41).

Background to watching-assessment-recognition

In contemporary practice nurses commonly rely on the term assessment alone as an umbrella term to describe how they identify and monitor patients' health-illness status. But, differentiating nursing's almost taken-for-granted watching responsibility is important because it can alert nurses to the earliest possible signals of patient deterioration. Likewise, differentiating the importance of recognising the meaning of watching and assessment data builds nurses' skill in acting quickly and appropriately to stop and reverse deterioration.

The importance of watching was emphasised in the 19th century nurses' descriptions of their work, especially night-watching. The nurses also recognised that watching had an important therapeutic quality in that it required attentiveness to patients. This point highlights the importance of the Therapeutic Milieu concepts in creating an enabling context for watching. The nurses considered watching just as important as formal assessment.

Originally, this concept was composed of watching and assessment alone, based on the historical documents. Recognition was added following discussion of the concept among nursing doctoral students who practiced in intensive care and step-down units.

The nurses argued that watching and assessment went only so far and that it was equally important to recognise the meaning of watching and assessment data. Further review of the historical documents indicated that the nurses' recognition of the meaning of watching and assessment data was implicit in the nurses' practice, thus recognition was added to watching and assessment to create the three-fold concept (Meehan, 2014).

Similarly, the concept of noticing (Watson & Rebair 2014, p. 514) can be thought of as integral in watching-assessment-recognition, emphasising the need for conceptual precision. Watson and Rebair propose that noticing is an art central to skilled nursing assessment and monitoring and essential to accurate clinical reasoning and decision-making. Failure to notice subtle cues to impending deterioration in patients' bio-physiological status can also result in failure to rescue patients from threats to their recovery, or to their life.

The Figure below can be used to visualise and think about how we experience and practice the on-going, integrally linked process of watching-assessment-recognition as one three-fold concept; one concept composed of three components.

The watching-assessment-recognition components

While watching-assessment-recognition is a composite, three-fold concept, examination of each of its components provides insight into the concept as a whole and how its components relate to one another.

Watching

Watching has long been a central aspect of nursing practice for the purpose of guarding vulnerable people from harm. Historically, nurses' watching of hospitalised patients was linked with guarding or "warding" of vulnerable people to protect them from harm.

Historically, the words guarding and warding had the same meaning (Porter, 1891). In hospitals warding patients was the responsibility of nurses and the locations where nurses warded patient were called wards. Thus, let us not forget that wards by definition are the domains of professional nurses and that the overall watching and care of patients in wards is nurse-led.

The term observation is commonly used in nursing practice literature, rather than watching. But watching is retained in Careful Nursing because of its specific meaning: to look attentively and expectantly at something over a period of time, especially something that changes (Watch, 2019).

Watching is a function of how nurses are in themselves just as much as it is a function of their objective practice. Thus, nurses engage in two types of watching; general, unitary (holistic), intuitive watching and specific, distinguishable reality, objective watching; often primarily utilising one or the other as their practice situation requires.

General, unitary (holistic), intuitive watching

Staff nurses especially engage in this inward type of watching and in the course of their practice can become highly skilled at this type of watching as part of their 24/7 engagement in nurse-patient relationships. Often, they appear to do this effortlessly or naturally and take this skill for granted.

There are few "mechanisms" as vital to hospitals' raison d'etre as staff nurses or teams of staff nurses engaged in this type of watching.

For example, a hospital ward staff nurse describes beginning his shift in a busy surgical ward by doing a quick round of his patients; most in 4-bed or 6-bed rooms. He has received shift handover and has a good objective knowledge of his patients' illness condition/medical diagnosis and their nursing condition/nursing diagnoses, and he checks this data as he greets each patient.

But also, as he enters each room, he "scans" his patients, registering in his inward mind's eye a "pattern" of each patient's condition. He carries these patterns in his mind's eye over his shift and each time he is in the vicinity of the given patients, whether attending to them or noticing them as he passes by them, he knows immediately whether any patient-pattern has changed in the direction of deterioration. He knows immediately if "something is not right" (Brier et al., 2014, p. 835).

Specific, distinguishable reality, objective watching

All levels of nurses engage in this outward type of watching, and advanced nurse practitioners utilise it especially, for example, when they need to assess how a patient's condition is being manifested in their outward, distinguishable bio-physical reality.

For example, a palliative care advanced nurse practitioner examines the status of one of her patients who has gradually developed mild dyspnea over the previous 24 hours. The nurse is well aware of her patient's medical diagnosis of metastatic bone cancer and treatments and nursing diagnoses and interventions. As she assesses her patient's vital signs, general appearance, CVS, Resp, PVS, Abdo, Skin, ECG & bloods, increased anxiety and fearfulness, she watches her patient closely noticing every nuance of her respiratory status.

The nurses' watching and noticing continually informs her clinical reasoning and decision-making, which along with tests/exams indicates progression in her patient's illness.

Nursing literature on watching

Only two articles which name watching directly as an aspect nursing practice appear in the literature, but both identify watching as a key nursing care process. Etherington (2014) writes about the importance of nurses "watching closely" (p. 13) acutely ill hospitalised patients under their care because these patients are at high risk of deteriorating or dying from conditions which can be treated. She observes that patients do not usually deteriorate suddenly and questions whether nurses can do more to detect deterioration early.

Etherington (2014) emphasises the importance of critical thinking in early detection of patient deterioration; she suggests that nurses could do more to detect patient deterioration at an early stage. At the same time, Etherington observes that the very stressful, high-workload conditions under which nurses' practice make it difficult for them to notice, assimilate and act quickly to prevent deterioration.

Further, Etherington (2014) insists that nurses must create for themselves surroundings which enable them to be alert to earliest indicators of patient deterioration. In Careful Nursing, the main purpose of the Therapeutic Milieu dimension is to create such surroundings.

Schmidt (2010) developed a grounded theory of "making sure" to describe the processes nurses use in "watching over" their patients (p. 400). The processes included knowing what's going on, being close, watching, not taking anything for granted, taking action as necessary and protecting. In a previous study Schmidt had found that hospitalised patients described nurses "watching over" them as being of central importance to them during their hospitalisation.

Throughout her study Schmidt (2010) equates watching with surveillance as a nursing intervention, noting that watching and surveillance have the same meaning. In fact, surveillance has become the word most commonly used in nursing literature concerned with watching patients to protect them from harm, followed by vigilance and sometimes monitoring. This situation explains the limited nursing literature on patient watching per se.

Watching as surveillance, vigilance or monitoring

Review of the origins of the words watching, surveillance and vigilance shows that all have the same origin and meaning, with watching entering English through German and surveillance and vigilance entering English through Latin and French (Partridge, 1977). Monitoring has a different origin linked to use of the mind and thinking, or critical thinking.

Review of nursing literature indicates that nurses began to use the term surveillance in the 1960s in relation to protecting patients from infection. However, most nursing research concerned with nurses' surveillance of patients does not mention watching (Shever et al., 2008, Fasolino & Verdin, 2015), except to describe surveillance activities to patients themselves (Dresser, 2012).

In 1992 surveillance was formally designated as a nursing intervention in the first edition of the Nursing Interventions Classification (Dougherty, 1992), where it is defined as "Purposeful and ongoing acquisition, interpretation and synthesis of data for decision making" (p. 500). Of the thirty-nine defined activities of surveillance as a nursing intervention, none specify watching patients whereas sixteen activities specify objective monitoring of patients. Thus, the meaning of surveillance has mostly come to mean monitoring patients' objective status with no reference to intuitive watching of patients.

Watching is encompassed in three articles which address vigilance in nursing practice. In an overview of the historical development of intensive care units in the United States, Fairman, (1992) identifies the traditional importance of "watchful vigilance" in monitoring critically ill patients. Prior to the introduction of technological monitoring, nurses recognised the importance of their role as "the alarm" that signalled deterioration (pp. 56-57). Fairman proposes that over a 40-year period during which technology was increasingly used to monitor patients' status in intensive care units, the importance of nurses' watchful vigilance and expertise was overshadowed, to the detriment of both patients and nurses.

Recently, O'Brien et al., (2018) developed a grounded theory of anticipatory vigilance to describe how nurses minimise risk and improve safety for perioperative patients. Nurses' engagement in mutual watching is proposed to enhance their anticipatory vigilance.

Meyer and Lavin (2005) address the importance of nurses' vigilance through the lens of caring theory and propose that "professional vigilance is the essence of caring in nursing" (Abstract). Vigilance is defined as a state of scientifically, intellectually, and experientially grounded watchful attention, calculation of risk to patients and readiness to act appropriately.

Meyer and Lavin (2005) view vigilance as the context within which nursing practice takes place, a context encompassing sustained attention and purposeful scanning of patients. This perspective and the understanding of vigilance as "the "watch-ful-ness" that is always a part of the nurse's thinking process" (para 2) closely approximates to the general, unitary (holistic), intuitive watching of Careful Nursing, described above.

Overall, watching in Careful Nursing is similar to vigilance; it is sometimes similar to surveillance but is different from surveillance as a monitoring-focused nursing intervention. Monitoring may reflect more specifically the critical thinking aspect of watching.

Assessment

A commonly accepted definition of nursing assessment is not readily identifiable in nursing literature (Penney et al. (2016), but it is generally accepted that nurses' assessment of patients, as a step in the nursing process, should be a structured, evidence-based process used to gather objective and subjective patient data in an organized way. It is emphasised that nurses' assessment of patients should be comprehensive and sensitive to the earliest possible detection of threats to patient safety (Douglas et al., 2016).

Logically, nursing assessment is guided by a nursing knowledge framework, for example a framework provided by a conceptual model or theory on nursing (Smith & Parker, 2015) or by Gordon's Functional Health Patterns (FHP) (Jones, 2013). However, nursing assessments in healthcare organisations usually follow body systems approaches (Considine & Currey, 2014). In addition, assessments are often focused around patients' chief complaint or medical diagnosis.

In conducting such medically-based assessments nurses overlook data which lead to understanding patients' total experience of illness and their responses to illness conditions, life process changes, and their health needs and potential over time; data necessary for making nursing diagnoses (Jones, 2013).

For Careful Nursing the Gordon's FHP (Gordon, 1994, 2008) patient assessment framework is most appropriate because it is nursing-specific, comprehensive, prioritises patient safety, and provides the data necessary for clinical reasoning and decision-making concerning nursing diagnoses, which in turn guide nursing care planning. The Gordon's FHP assessment structure relates directly to Careful Nursing's use of the standardised nursing languages of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses (Herdman & Kamitsuru, 2018), Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) (Moorhead et al., 2018), and Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (Butcher et al., 2018).

Gordon's Functional Health Patterns (FHP) assessment

(Gordon's FHP assessment definitions to be added here)

Recognition

Recognition, as we are concerned with it in nursing practice, is identification of something through the perception of sameness to something previously known or encountered. "Re-cognition" means "to know again, or recall to mind" (Recognition, 2019). In relation to nursing watching and assessment, recognition is an act of identifying correctly the meaning of perceptions and experiences of patients and patient assessment data, based on knowledge and previous experience.

The importance of recognition is consistently recognised in nursing assessment literature and especially in watching literature (Schmidt, 2010). Fasolino and Verdin (2015) and Dresser (2012) emphasise the particular importance of recognition in watching patients for signs of physiological deterioration. Meyer and Lavin (2005), in their definition of vigilance or watch-ful-ness as the essence of caring emphasise the importance of recognising patterns of patient's behaviour.

The nature and importance of recognition highlight the fact that comprehensive knowledge and active intellectual engagement are major factors in enabling recognition. In relation to patient safety, this applies to rapid recognition of patients' condition and any deterioration that occurs. In preparation for making nursing diagnoses, recognition requires a good knowledge of the defining characteristics and related factors of a range of nursing diagnoses.

There can also be an inverse use of recognition in a situation where we are seeing and, or, experiencing something not encountered before; this would flag the need to act quickly to get other opinions. In terms of preparing to make nursing diagnoses it could be the beginning of working toward developing a new diagnosis. In both cases it could also mean that our knowledge base requires further development.

Recognition has many practical implications for nurse education as well as for practice management. In management for example, threats to patient safety could result from moving nurses to different practice areas to 'cover a shift' when there is a shortage of nurses. Transfer of nurses to practice areas where they have had little or no recent experience with particular types of problems patients are experiencing could limit their ability to recognise early indicators of deterioration.

The nature of recognition can explain why nurses generally are uncomfortable with being unexpectedly transferred to different practice areas, and also has implications for the use of bank or agency nurses.

Watching-assessment-recognition: in summary

Watching-assessment-recognition is an exceptionally complex, three-fold concept; its three components are both distinctive and folded into one another and encompass both the art and science of professional nursing practice. This concept highlights the powerful and centrally important 24/7/365 role of professional nurses as guardians of patient safety, especially in hospitals but also in helping people maintain their health in their home, both in person and through virtual care systems.

The watching-assessment-recognition role of professional nurses in the health service is so vitally important in protecting sick, injured and vulnerable people from harm that, paradoxically, it is often taken for granted by the medical profession (O'Brien 2016) and by government health departments, taken their restrictions on professional nurse staffing levels.

As nurses, we must be alert to the importance and complexity of our watching-assessment-recognition responsibility and not take it for granted ourselves. Some literature reviewed above suggests that we should always be asking ourselves whether we are doing enough to fully implement this important concept.

Your watching-assessment-recognition self-rating:

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your skill in intuitive watching of your patients?

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your objective watching of your patients?

In your formal assessment of patients, are you guided by a nursing knowledge framework, rather than by a body systems framework?

In your formal assessment of patients, are you primarily focused on their holistic nursing needs, rather than their chief complaint or medical diagnosis/es?

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your ability to recognise the meaning of your patient watching and assessment data?

Based on your assessment of your current skill in watching-assessment-recognition, decide what you will do to further develop your skill in implementing this concept.

Make your own 'I will' statements . . .

Examples of watching-assessment-recognition 'I will' statements:

. . . work on deepening my holistic, intuitive watching of patients by

. . . work on deepening my holistic, intuitive watching of patients by

comparing what I "see" with what colleagues "see"

. . . sharpen my ability to notice things about patients by making lists of

things I notice

. . . focus on watching and assessing patients themselves as well as data

recorded on monitoring equipment attached to them

. . . frequently test my ability to quickly recognise the meaning of patient data

References

Brier, J., Carolyn, M., Haverly, M., Januario, M. E Padula., C. Tal, A., & Triosh, H. (2014). Knowing 'something is not right' is beyond intuition: development of a clinical algorithm to enhance surveillance and assist nurses to organise and communicate clinical findings. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 832–843.

Butcher, H. K., Bulechek, G. M., Dochterman, J. M. M., & Wagne, C. (Eds). (2018). Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (7th ed.). St. Louis, MI: Elsevier Inc.

Carpenito, L J. (2017). Nursing Diagnosis: Application to Clinical Practice (15th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Considine, J., & Currey, J. (2014). Ensuring a proactive, evidence-based, patient safety approach to patient assessment. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 300-307.

Dougherty, C. M. (1992). Surveillance. In J. C. McCloskey & G. M. Bulechek (Eds.), Nursing Interventions: Essential Nursing Treatments (2nd ed.) (p. 500). Philadelphia: W.B Saunders.

Douglas, C., Booker, C., Fox, R., Windsor, C., Osborne S., & Gardner G. (2016). Nursing physical assessment for patient safety in general wards: reaching consensus on core skills. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 1890-1900.

Dresser, S. (2012) The role of nursing surveillance in keeping patients safe. Journal of Nursing Administration, 42, 361-368.

Etherington, L. (2014). Watching Closely? Nursing Management, 21(2), 13.

Fasolino, T., & Verdin, T. (2015). Nursing surveillance and physiological signs of deterioration. MEDSURG Nursing, 24, 397-402.

Garvey, P. K. (2015) Failure to Rescue: The Nurse's Impact. MEDSURG Nursing, 24, 145-149.

Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing Diagnoses Definitions and Classifications 2018–2020. New York, NY: Thieme Publishers.

Jones, D. A. (2013). Nurse-patient relationship: Knowledge transforming practice at the bedside. In J. I. Erickson, D. A. Jones, & M. Ditomassi, (Eds.). Fostering Nurse-Led Care (pp. 85-121). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Meehan, T. C. (2014) The Careful Nursing Philosophy and Professional Practice model: Overview and revisions. Careful Nursing News, 5(4), 10-11.

Meyer, G., & Lavin, M. A. (2005). Vigilance: The essence of nursing. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 10 (1).

Moorhead, S., Swanson, E., Johnson, M. & Maas, M. L. (Eds.). (2018) Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC), (6th ed.). St. Louis, MI: Elsevier Inc.

O'Brien, B., Andrews, T., & Savage E. (2018). Anticipatory vigilance: A grounded theory study of minimising risk within the perioperative setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 247–256.

O'Brien, E. (2016, December 19). Now I see the true value of nurses. The Sunday Times [Irish Edition], p. 4.

Partridge, E. (1977) Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. New York: Routledge.

Penney, W., Poulter, N., Cole C., & Wellard, S. (2016). Nursing assessment of older people who are in hospital: exploring registered nurses' understanding of their assessment skills. Contemporary Nurse, 52, 313-325.

Porter, N. (Ed.) (1891). Webster's International Dictionary of the English Language. Springfield, MA: C. Merriam & Co.

Shever, L L., Titler, M. G., Kerr, P., Qin, R., Kim, T., & Picone, D. M. (2008). The effect of high nursing surveillance on hospital cost. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40, 161-169.

Smith, M., & Parker, M. E. (2015) Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice (4th ed.). Philadelphia PA: F. A. Davis Company.

Watch. (2019) https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/watching

Watson, F., & Rebair, A. (2014). The art of noticing: essential to nursing practice. British Journal of Nursing, 23, 514-517.

Therese C. Meehan© July 2020