Nursing Diagnosis-outcomes-interventions

In a nutshell . . . .

In this page you're introduced to the Diagnosis-Outcomes-Interventions idea of the Practice Competence and Excellence (PCE) dimension. Note that these are NURSING Diagnosis-Outcomes-Interventions. We still at times need to be reminded of this because for so long we focused only on medical diagnoses, outcomes and interventions, which are of course vitally important. But nursing diagnoses, outcomes and interventions are also vitally important.

This idea is the fourth of the four ideas that make up the PCE critical circle of clinical responsibility. It is intertwined with the other three ideas of the critical circle of clinical responsibility, discussed in the previous three pages.

You'll find that this page is quite long because Diagnosis-Outcomes-Interventions use standardised nursing languages. You'll be introduced to arguments for and against using nursing diagnoses and standardised nursing languages.

You'll see that Careful Nursing uses the NANDA-I, NOC and NIC languages because research shows they are by far the best. You'll find a lot of detail about what these languages look like and how they work.

You'll find an illustrated practice example of the great improvement NANDA-I can make in detailing nursing care and making it visible. You'll find details and examples of how NANDA-I diagnoses work with NOC outcomes and NIC interventions, and an example what a hospital semi-electronic NANDA-I, NOC care plan looks like.

Introduction

Diagnosis-Outcomes-Interventions is the sixth concept of the Practice Competence and Excellence (PCE) dimension and the last of the four PCE concepts that form the Careful Nursing critical circle of clinical responsibility.

This concept is intertwined with the other three concepts of the critical circle of clinical responsibility; watching-assessment-recognition, clinical reasoning and decision-making, and patient engagement in self-care.

Before continuing, please take a minute to review the two figures on the PCE Introduction page above to remind yourself how this concept relates to the other seven PCE concepts (first Figure) and where it fits in the critical circle of clinical responsibility (second Figure).

Diagnosis in this concept, of course, refers to nursing diagnosis, not medical diagnosis. Nursing diagnosis, outcomes and interventions are standardised nursing languages/terminologies (SNL/Ts) which are used in Careful Nursing to structure patient care planning, that is, what is often thought of as the nursing process. There are seven recognised SNL/Ts (Tastan et al. 2014). Three specific languages are used in Careful Nursing.

Careful Nursing uses NANDA-I nursing Diagnoses (Herdman & Kamitsuru 2018) to describe patients' nursing problems/needs, the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) (Moorhead et al. 2018) to describe outcomes sought for patient's nursing problems/needs, and the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (Butcher et al. 2018) to describe nursing practices used to resolve or treat patients' nursing problems/needs.

Careful Nursing uses these NANDA-I, NOC and NIC SNL/Ts because they are evidence-based, the most supported by nursing research, directly applicable in clinical practice and are the most widely used SNL/Ts internationally (Tastan et al. 2014).

Valid and reliable use of NANDA-I, NOC and NIC depend on skilled implementation of the watching-assessment-recognition and the clinical reasoning and decision-making concepts (see previous PCE pages).

Implementation of NANDA-I, NOC and NIC must be based on initial/hospital admission comprehensive nursing assessment, if possible guided by a Gordon's Functional Health Patterns (Jones, 2013), rather than by a medical model assessment.

It has become evident that initial implementation of NANDA-I, NOC and NIC in hospitals, especially when nurses have not learned these languages in their education programmes, requires some standardisation within medically designated patient groups.

However, every effort must be made to prevent use of these languages becoming only a technical, time-saving documentation method without any reference to individual human responses and patient needs. NANDA-I nursing diagnosis-guided care plans must provide for undesirable human responses experiences by individual patients and must allow for clinical nurses' judgements about patient outcomes and nursing interventions.

Historical note

The NANDA-I nursing diagnosis, NOC and NIC SNL/Ts best represent in contemporary terms the practice of the early to mid-19th century nurses. The documents describing the early nurses' practice show that they identified patients' nursing problems/needs accurately, they developed specific nursing interventions, and their circumstances required that they demonstrate clearly the effectiveness of their practice, especially to the British Crimean War office. It can be argued that their practice foreshadowed the contemporary development of NANDA-I nursing diagnosis, NOC and NIC.

Background of SNL/Ts

SNL/Ts have developed gradually over time beginning with use of the term nursing diagnosis.

In a 1953 issue of the American Journal of Nursing, Fry wrote about use of nursing diagnosis as a creative approach to nursing practice. Fry proposed to nurses that: "the first major task in our creative approach to nursing is to formulate a nursing diagnosis and design a plan which is individual and which evolves as a result of a synthesis of needs" (p. 302). Over the following 20 years the term nursing diagnosis gradually began to replace the term nursing problem and the nursing process was raised to a higher level of critical thinking, reasoning and decision-making – but not without much debate.

Arguments against nursing diagnosis

Some nurses considered the idea of a nursing diagnosis too abstract, that it obstructed the flow of clinical practice, that academic teaching of nursing diagnosis did not transfer to clinical practice and observed that there was no agreement about how diagnoses were classified (Johnson & Hales, 1989). Nursing diagnosis was considered too technical for use by a caring profession and too time-consuming. Nursing diagnosis is still sometimes associated with objectifying patients and viewed as an example of the medicalisation of nursing (Clarke, 3013).

Arguments for nursing diagnosis

Other nurses proposed that for professional, political and economic reasons nurses must be able to name what they do clearly, accurately and consistently. Regarding nursing practice, Clarke and Lang (1992) argued that "If we cannot name it, we cannot control it, finance it, teach it, research it, or put it into public policy" (p. 109).

The benefits of nursing languages, including diagnosis, gradually became fairly widely recognised, for example, "better communication among nurses and other health care providers, increased visibility of nursing interventions, improved patient care, enhanced data collection to evaluate nursing care outcomes, greater adherence to standards of care, and facilitated assessment of nursing competency" (Rutherford, 2008, p.1.).

Embedding diagnosis into nursing practice

In 1972 the expectation that nurses make nursing diagnoses was included for the first time in a United States Nurse Practice Act, that of New York state; 'diagnosing and treating human responses to actual or potential health problems' became part of the legal domain of professional nursing (Jarrin, 2010, p. 167). In 2009 the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association–International (Herdman & Kamitsuru 2018) took up this creative work and made it global.

Along with NOC and NIC NANDA-I invited all nurses to join them in their effort to provide for our profession the ability to name our practice clearly and accurately, to measure nursing-sensitive patient outcomes, strengthen our control over our practice, enhance our professional identity, and firmly establish our professional nursing authority.

Languages versus terminologies

As eHealth records have become a reality use of the term languages is increasingly replaced by terminologies. The terms are now used interchangeably. NANDA-I and NIC are mapped into global healthcare language SNOMED CT, ensuring that they can be used in eHealth records. NOC is currently being mapped into SNOMED CT. Unless nursing languages/terminologies are available for use in eHealth records. nursing practice would become invisibly mapped into medical practice.

Meaning of diagnosis

Diagnosis: The term diagnosis has its root meaning in the Greek word for distinguish (Diagnosis, 2019). To make a diagnosis means to make a "judgement based on critical perception or scrutiny"; a judgement "based on scientific determination" (Porter, 1891, p. 405).

Following Porter and Gallagher-Lepak (2018), making a nursing diagnosis is the art or act of making a clinical nursing judgement which involves recognising the presence of undesirable human responses, or susceptibility to such responses, to sickness, injury or a stage of the life process (for example, adolescence or older adulthood).

Making a nursing diagnosis also includes making a clinical nursing judgement concerning patients, families and communities motivation and desire, or need for motivation and desire, to increase their health and well-being and realise their health potential.

Differential diagnosis: Equally important is the term differential diagnosis; "the determination of the distinguishing characteristics as between two similar [undesirable human responses]" (Porter, 1891). For example, is a patient experiencing fear or anxiety? Is a patient's breathing problem, ineffective airway clearance or impaired gas exchange?

Making a nursing diagnosis is founded in critical thinking and encompasses watching-assessment-recognition, clinical reasoning and decision-making, in collaboration with patient engagement in self-care (as possible) – in action. There is every reason for nursing to be just as discerning and accurate in its practice as medicine (formerly almost exclusively associated with use of the term diagnosis).

What is a NANDA-I nursing diagnosis?

A NANDA-I nursing diagnosis is a clinical judgement concerning an "undesirable human response" or "susceptibility ... for developing an undesirable human response to health conditions/life processes" (italics original) (Gallagher-Lepak, 2018; p. 35). A nursing diagnosis is not the condition or life process event itself.

For example, a person's health condition may be a stroke, diagnosed and treated by medicine. Related nursing diagnoses will be the person's undesirable human responses to the stroke health condition, such as feeding self-care deficit or impaired mobility. A patient's life process may, for example, be adolescence. Undesirable responses to adolescence may be ineffective coping or disturbed body image.

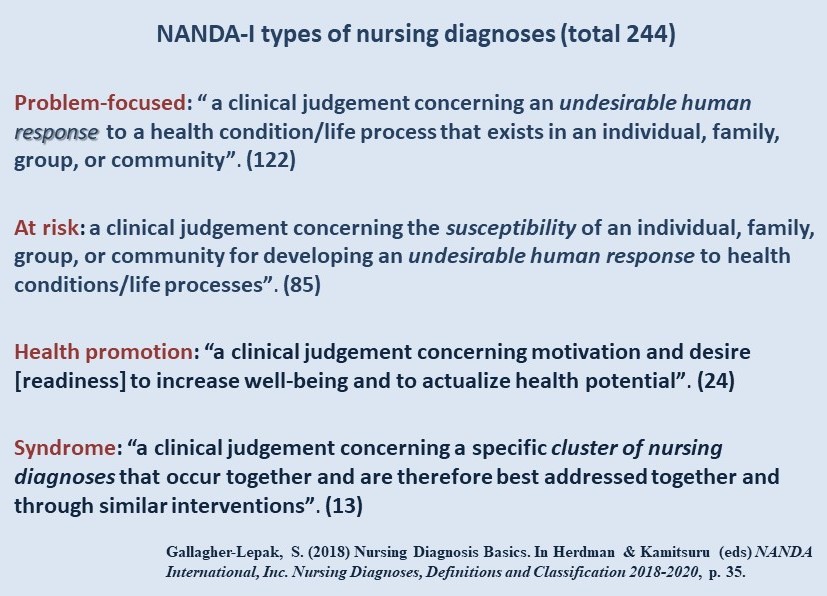

Types of NANDA-I nursing diagnosis

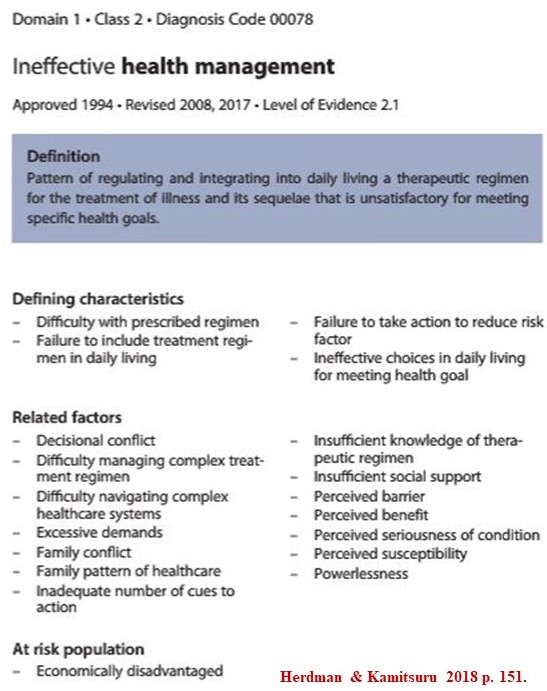

There are four types of nursing diagnosis which encompass the range of undesirable human responses, susceptibilities, as well as motivations to increase well-being in sick, injured and vulnerable people, shown in the following Figure:

The 244 approved diagnoses are organised in 13 categories (called domains) which align with the 11 Gordon's Functional Health Patterns (Gordon, 1982) (see the watching-assessment-recognition page above). Each category is sub-organised into classes. Each class contains class-specific diagnoses, for example as shown in the following Figure:

.jpg)

What do NANDA-I nursing diagnoses look like?

For a full basic look at and understanding of a NANDA-I diagnosis, read and re-read the brief Nursing diagnosis basics chapter (Gallagher-Lepak, 2018) in Nursing Diagnoses Definitions and Classifications 2018–2020 (Herdman & Kamitsuru, 2018).

As shown above, most NANDA-I nursing diagnoses are problem-focused diagnoses and somewhat fewer are at-risk diagnoses. Only 10% of diagnoses are health promotion diagnoses, however taken the importance of health promotion and increasing emphasis on provision of health care in communities to reduce the need for acute hospital-based care, health promotion diagnoses will become increasingly important.

Problem-focused diagnoses

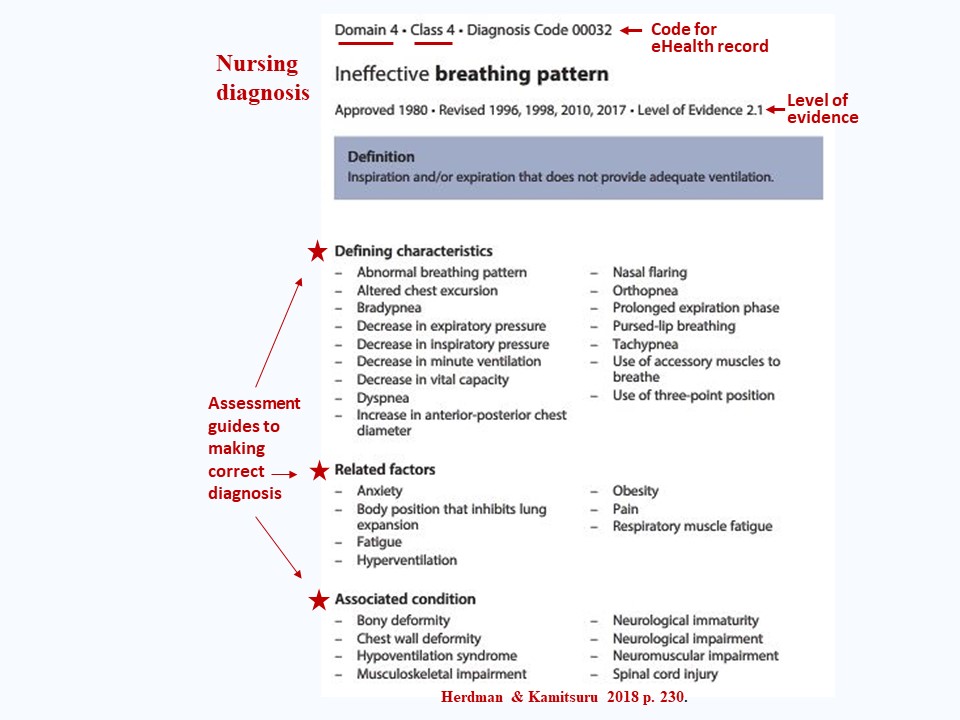

The following Figure shows an example of a problem focused diagnosis from Herdman & Kamitsuru (2018):

Across the top notice the category (domain 4: which is activity/rest) and sub-category (class 4: which is cardiovascular/pulmonary responses), and the code number that represents this diagnosis in the electronic system of an eHealth record.

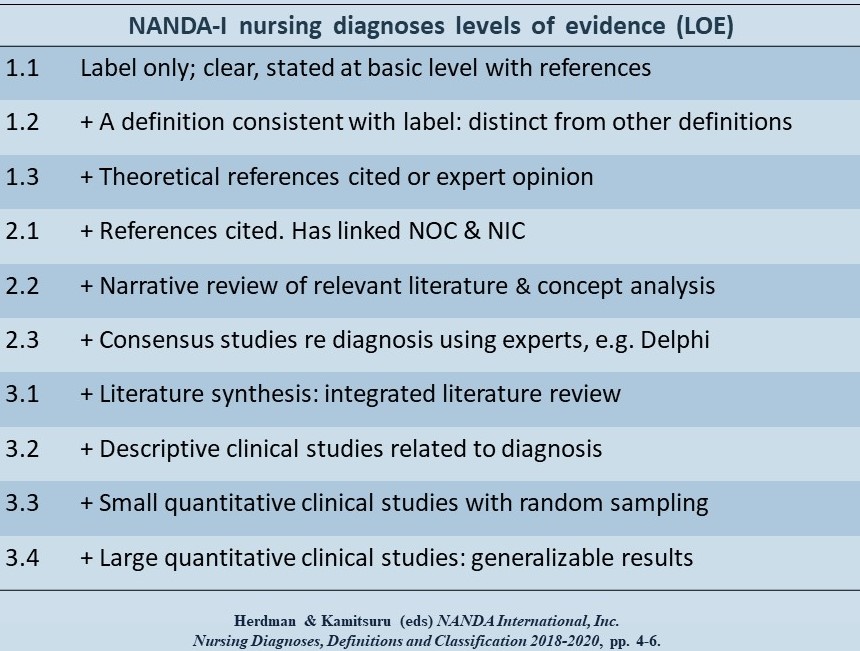

Then you see the diagnosis name (label) and, underneath the name, the history of the development of this diagnosis; very importantly for evidence-based practice, notice the level of evidence (LOE) for this diagnosis. (LOEs are illustrated and discussed with the LOE Figure further down this page).

Notice the definition of the diagnosis, the first step in developing a diagnosis.

Then notice the all-important defining characteristics, related factors and associated conditions which are indicators of this diagnosis. These diagnosis indicators will be critically scrutinised in the patient assessment and used to make a judgement that this is most accurate diagnosis for a particular patient (review meaning of Diagnosis above).

Not all diagnosis defining characteristics, related factors and associated conditions need to be present in a patient to make a diagnosis, but only enough to indicate that this is the most accurate diagnosis for the patient and that its indicators differentiate it from other diagnoses which may appear to fit the patient's problem but are actually not the correct diagnosis.

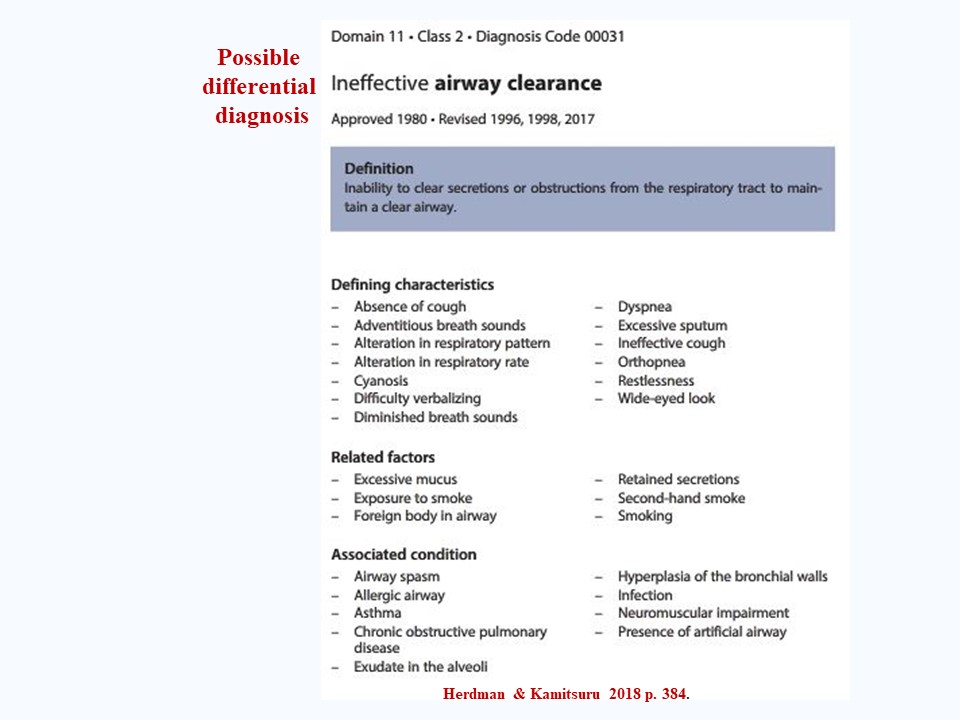

A diagnosis must be compared with possible differential diagnoses to ensure it is the correct diagnosis. For example, one differential diagnosis for a patient with a breathing problem is shown in the following Figure:

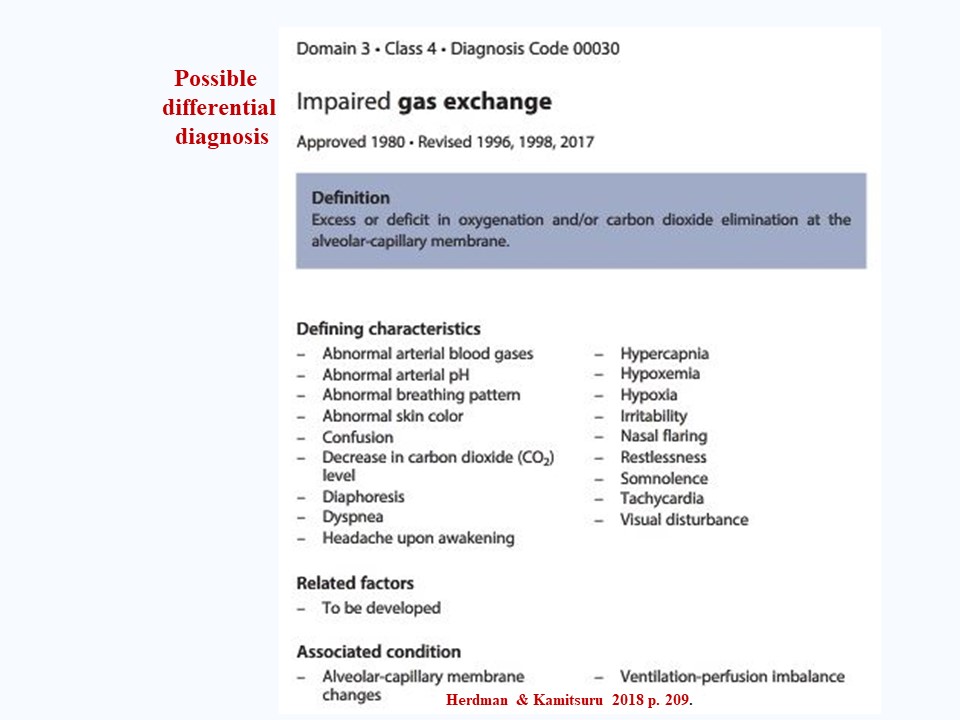

Another differential diagnosis for a patient with a breathing problem is shown in the following Figure:

Notice how in the three Figures immediately above (examples of breathing problem diagnoses) the diagnoses' defining characteristics, related factors and associated conditions differ. Using these indicators, similar diagnoses are examined and differentiated to help ensure that the correct diagnosis is made.

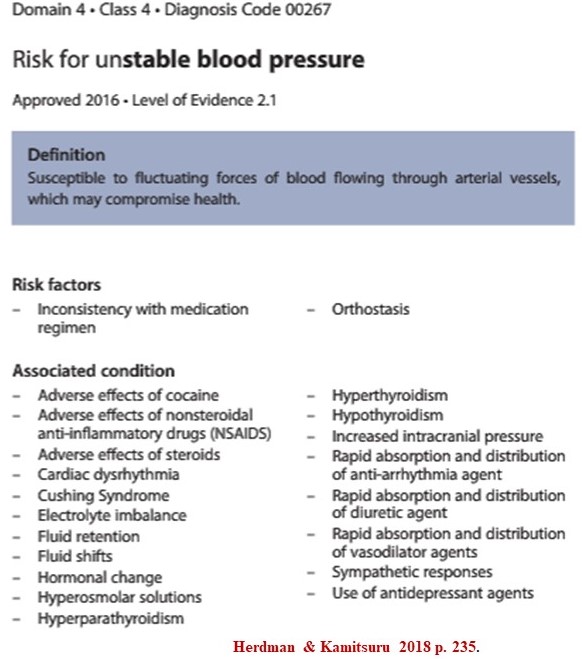

At risk diagnoses

The definition of an at risk diagnosis appears in the Types Figure above. The following Figure shows an example of an at-risk diagnosis from Herdman & Kamitsuru (2018) concerning susceptibility to an unstable blood pressure:

Notice that the diagnosis is made according to risk factors and associated conditions which increase a patients susceptibility to having an unstable blood pressure. The diagnosis alerts nurses to specific watching-assessment-recognition regarding this susceptibility.

Health promotion diagnoses

The definition of a health promotion diagnosis appears in the Types Figure above. The following Figure shows an example of a health promotion diagnosis from Herdman & Kamitsuru (2018) concerning ineffective health management:

Notice that this diagnosis is made according to defining characteristics, related factors and at risk populations. Good watching-assessment-recognition will identify this diagnosis as early as possible in a patient's care process so that its indicators can be systematically evaluated and the best possible health management plan developed.

Diagnoses levels of evidence (LOE)

As noted above NANDA-I diagnoses are evidence-based and are supported by different levels of evidence, as shown in the following Figure:

Note that levels of evidence begin at the minimum 1.1 level and range up to the maximum 3.4 level.

Note that levels of evidence begin at the minimum 1.1 level and range up to the maximum 3.4 level.

Most diagnoses are at least at the 2.1 level, which means that they are supported by research and other literature.

This literature supporting each diagnosis is available at the Media Center of the Thieme Publishing Company, publishers of Nursing Diagnosis Definitions and Classifications 2018–2020 (see access below under NANDA-I diagnosis resources). If this level is not increased for a given diagnosis within a certain period of time the diagnosis may be removed from the list of approved diagnoses.

Opportunity for much-needed nursing research

The need for research to strengthen levels of evidence for NANDA-I diagnoses provides an excellent opportunity for Masters degree level research. Bringing a diagnosis from the 2.1 level of evidence to a 2.2, 2.3, or 2.4 level of evidence is well within the scope of a Masters level research project; such research findings would be very relevant for clinical practice and likely to be accepted for publication.

As indicated by the concept diagnosis-outcomes-interventions, making NANDA-I nursing diagnoses is the first step in patient care planning.

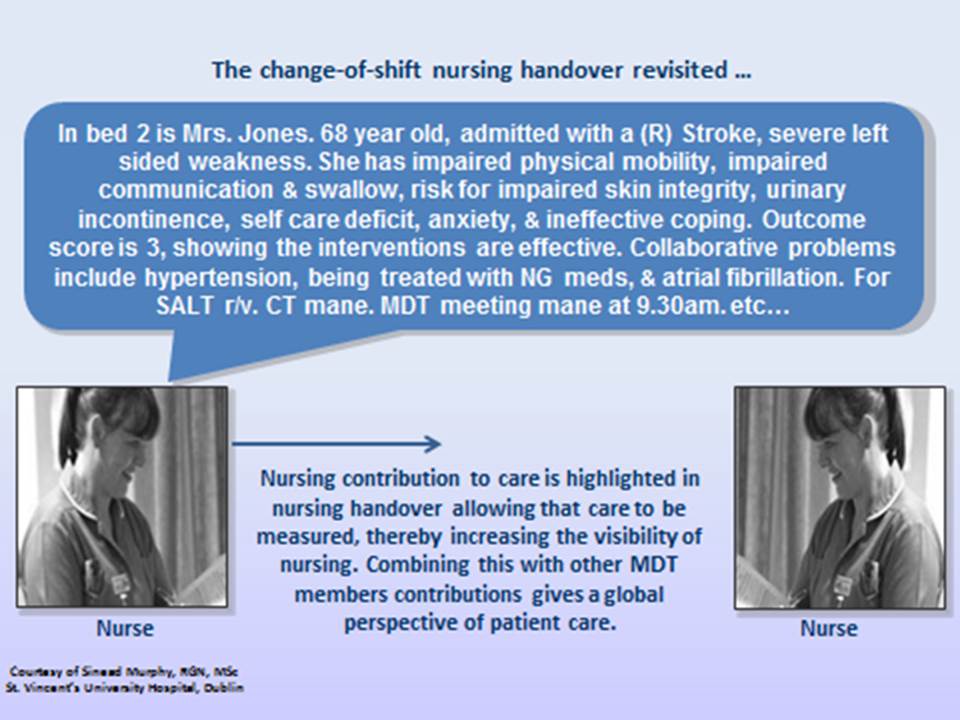

Use of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses to guide care planning in Careful Nursing has proved to be very beneficial at an essential practice level. As proposed by Clarke and Lang (1992), quoted above, nurses' ability to name their practice has made their practice objectively visible to them, to members of other health professions, and to the individuals and families they care for. Nurses ownership and control of their practice has increased, as has their adherence to hospital documentation standards (Murphy et al. 2018).

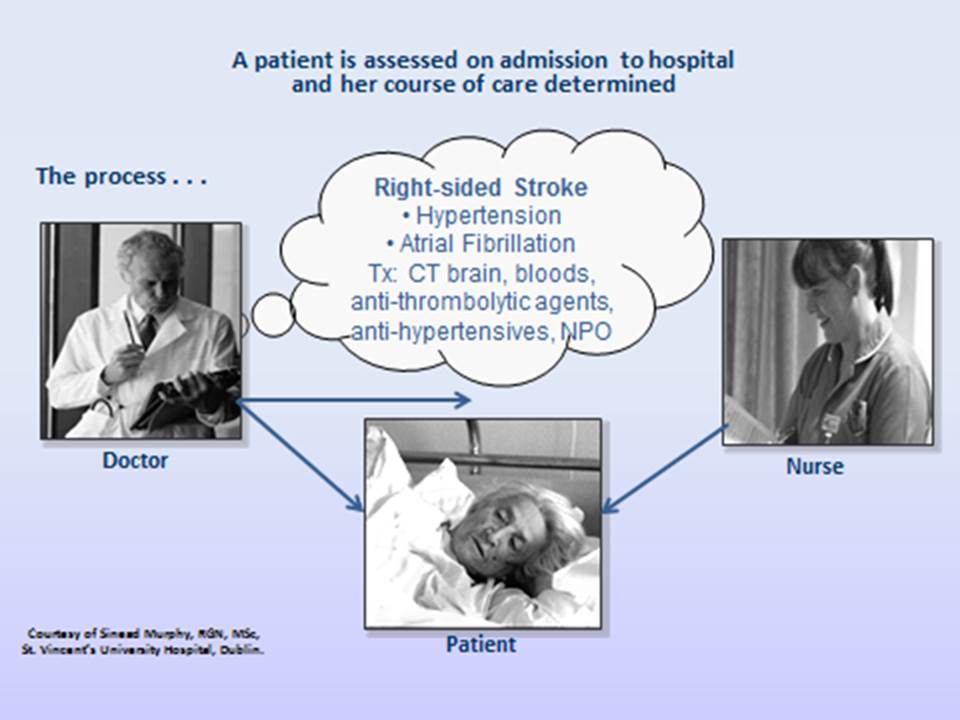

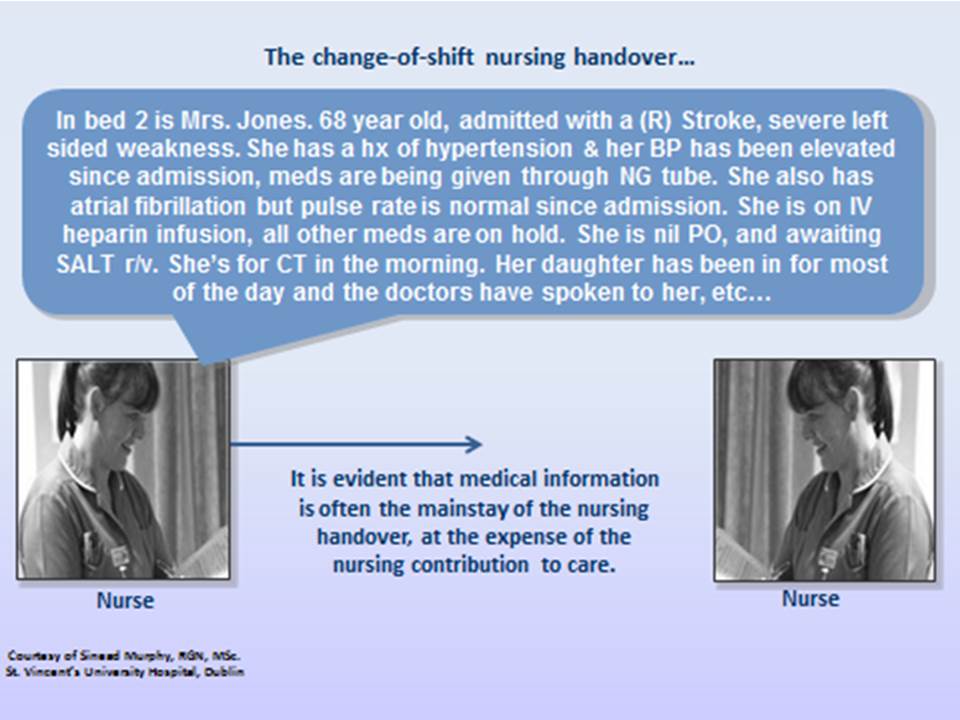

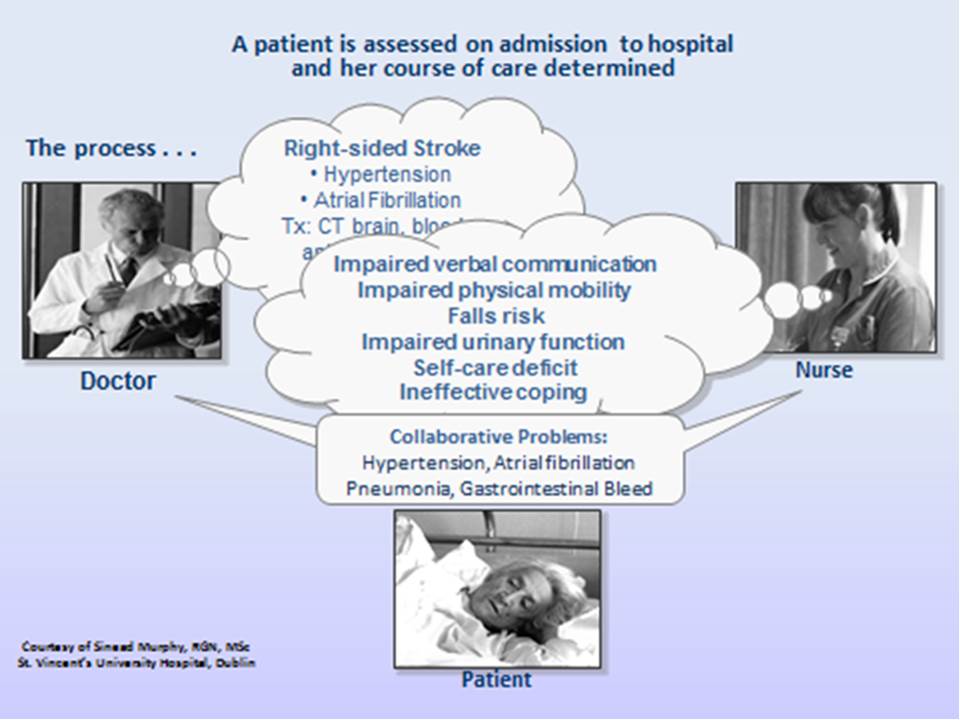

These benefits are illustrated in the following NANDA-I nursing diagnoses "before and after" examples constructed by Sinead Murphy, a former Senior Project Manager for a Careful Nursing implementation project.

Example of how nursing diagnosis changes nurses approach to patient care

This first example illustrates what happens when NANDA-I nursing diagnoses are not used: :

The second example illustrates what happens when NANDA-I nursing diagnoses are used:

NANDA-I nursing diagnosis resources

Further resources include the key NANDA-I publication, Nursing Diagnoses Definitions and Classifications 2018–2020 (Herdman & Kamitsuru, 2018). This is a "must read" book.

In addition, the Thieme Publishing Company Media Center offers a range of free resources which may be accessed at MediaCenter.Thieme.com https://mediacenter.thieme.com/ When prompted during the registration process enter the following code: XZ88-D7XB-SJK6-QE85

What is a NOC nursing outcome?

.jpg)

NOC outcomes are categorised according to seven types of health-related domains, for example, functional health, physiologic health and family health. Each domain is sub-categorised into a total of 32 classes, for example, the functional health domain has four classes: energy maintenance, growth & development, mobility and self-care (Moorhead et al. 2013).

Each outcome has a definition, an eHealth record code (although NOC is not yet mapped to SNOMED CT), a list of measurable indicators of outcome status, a total measurement outcome status measurement scale, and a target outcome rating scale. Each outcome is measured using a five-point Likert-type scale, on which a rating of 5 is always the best possible score and 1 always the worst possible score.

NOC has a complex set of 20 types of measurement scales and a further set of six combined measurement scales which cover a wide range of types of nursing-sensitive outcomes in patients, caregivers, families and communities. But, this complex system of scales is not easily illustrated.

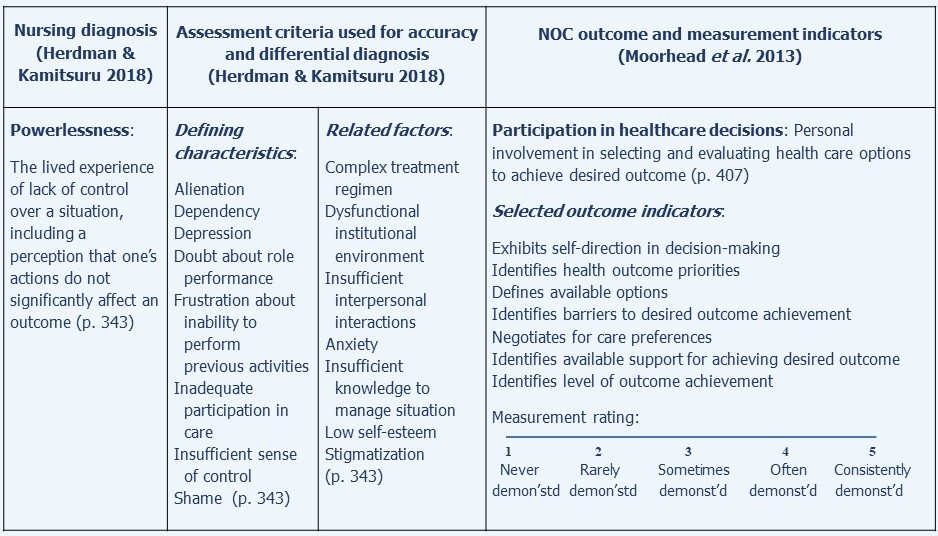

NOC nursing-sensitive outcomes are relatively easily linked to NANDA-I nursing diagnoses. A simple example of a modified NOC outcome, Participation in healthcare decisions, along with the NANDA-I diagnosis of Powerlessness to which it is related, to is shown in the following Figure:

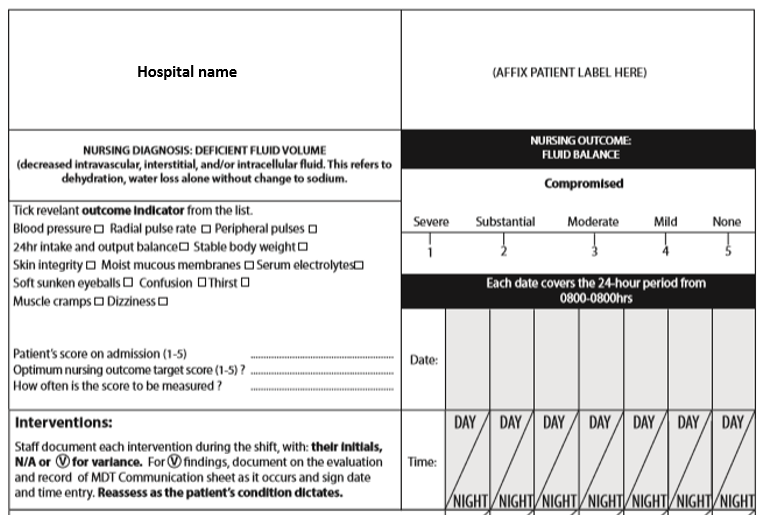

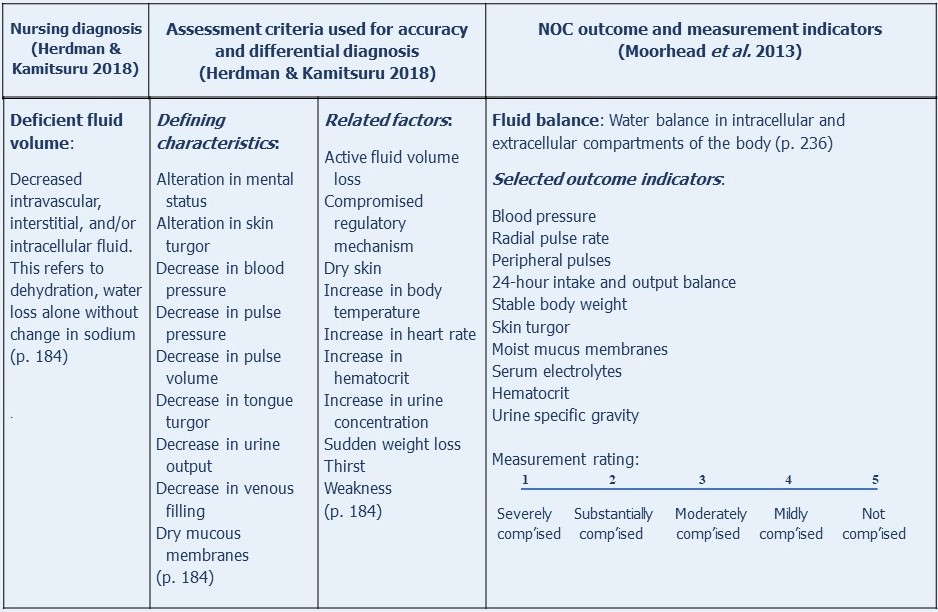

Another simple example of a modified NOC outcome, Fluid balance, along with the NANDA-I diagnosis, Deficient fluid volume, to which it is related, is shown in the following Figure:

As indicated by the concept diagnosis-outcomes-interventions, selecting appropriate nursing outcomes is the second step in patient care planning.

As soon as a NANDA-I diagnosis is made, its most appropriate NOC outcome is selected and measured to provide a baseline outcome measurement.

As with the use of NANDA-I nursing diagnosis, patients, caregivers, families and/communities are encouraged to participate in selection of NOC outcomes and their measurement.

The complexity of the NOC outcomes classification does not lend itself to practically manageable integration into the paper semi-electronic nursing care plans currently used in Careful Nursing hospitals in Ireland. Experience has demonstrated the NOC outcomes require some modification of the number of stated indicators, even though such modification may compromise the validity and reliability of the measurements.

When a NOC outcome is sought in relation to a NANDA-I diagnosis, the NOC textbook is explored to seek an appropriate outcome(s). When the outcome is selected some time needs to be taken to examine the outcome in detail and merge it into the care plan in the best practically manageable way.

The two Figures above and the example of a semi-electronic paper care plan shown in the summary section below show how NOC has been required to be modified in Careful Nursing semi-electronic paper care

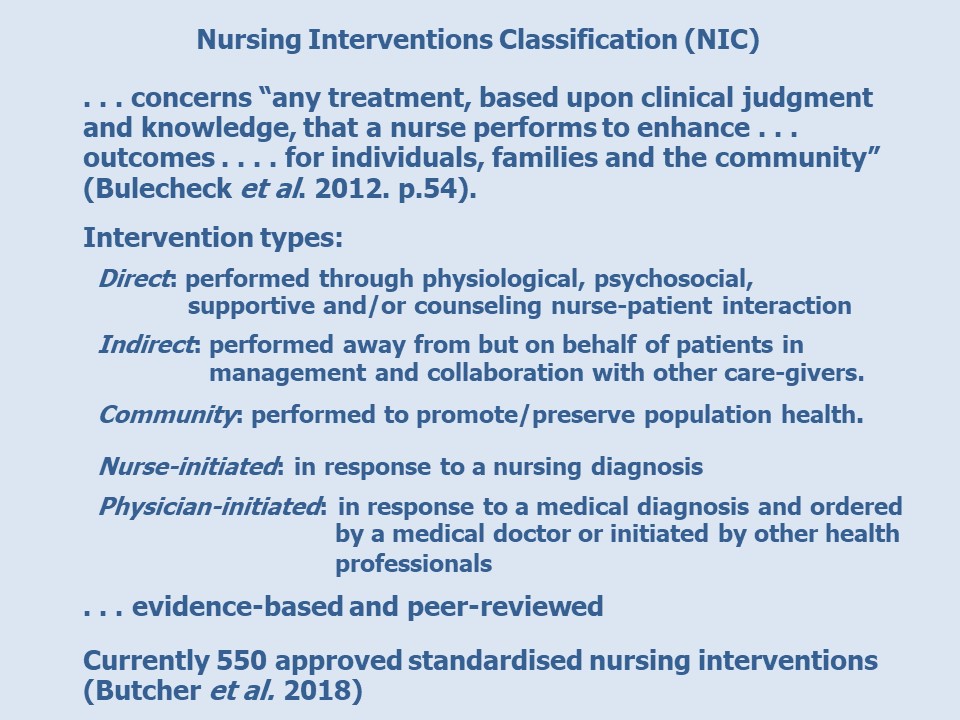

What is a NIC nursing intervention?

NIC interventions are categorised according to seven domains concerning, for example, basic physiological, complex physiological, behavioural, safety, family and community. Each domain is sub-categorised into classes ranging from two (safety) to six (behavioural) classes. Classes narrow the specificity of the interventions, for example the safety classes are crisis management and risk management. The NOC interventions are then listed according to classes.

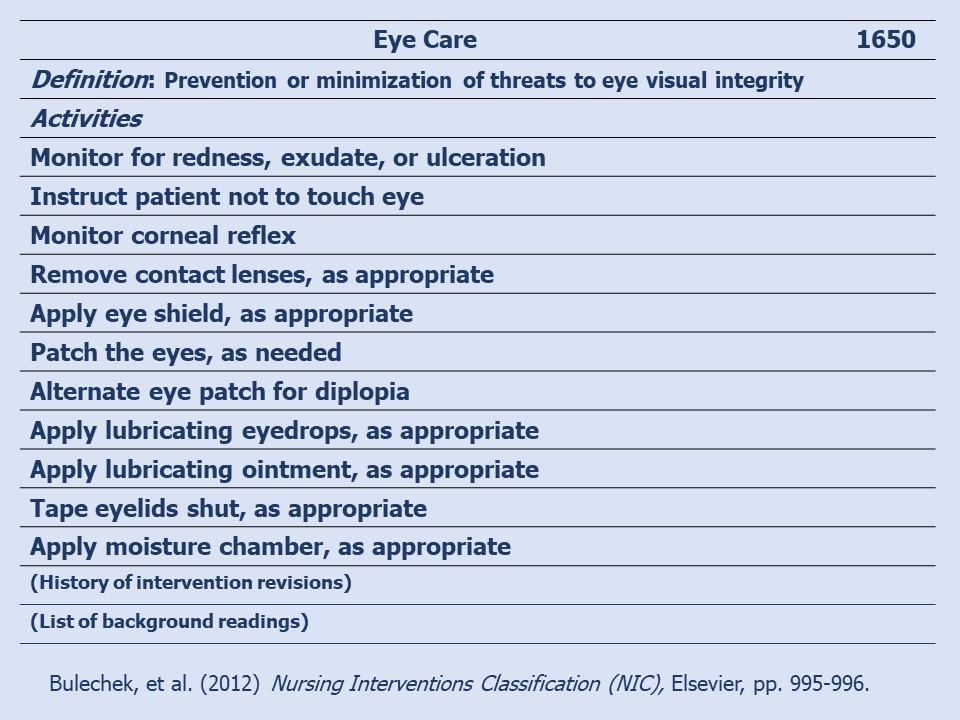

An example of a simple intervention, Eye Care, is shown in the following Figure to illustrate the structure of an intervention. Notice at the top the intervention name and eHealth record code number. Then the intervention definition is given and the intervention activities listed. Finally, the history of the development of the intervention is indicated, and the supporting references from the literature are listed.

Another example of a nursing intervention, Hypertension Management, is illustrated on the University of Iowa NIC webpage: http://www.nursing.uiowa.edu/sites/default/files/documents/cnc/Hypertension_Management.pdf

Flexibility of NIC interventions

Butcher et al. (2018) emphasise that only an intervention name and definition are standardised and that, when an intervention is used, the name and definition should not be changed. The lists of interventions' activities are not standardised but they must be consistent with the definition of the intervention. In practice settings activities from the list are selected as appropriate to the setting and setting-specific activities are added. Added activities should be congruent with the definition of the intervention, supported by literature and evidence based.

NIC interventions estimated time and education levels

The NIC book, Nursing Interventions Classification (Bulechek et al. 2012) provides a very useful section called Estimated time and educations level necessary to perform NIC interventions. For example, the time estimated to perform Eye Care, shown above, is given as "15 minutes or less" and the minimum education level given is "RN basic" (p. 2625).

There are obvious benefits to estimated times taken to perform an intervention. The estimated minimum education levels given to perform an intervention are categorised as Nursing assistant, RN basic (any education level required for professional nurse registration), and RN post-basic (any specialised education beyond the professional nurse registration level - apparently not limited to nursing education). These very broad categories reflect NIC's international audience.

The educational levels for performing interventions can be aligned with the professional scope of practice in given countries. The inclusion of the nursing assistant level could be useful for determining whether to delegate a professional nursing responsibility to a nursing assistant (for which the professional nurse would still be responsible). At the same time, it is disappointing that professional nursing is referred to as a job as in "job responsibilities". Surely practice responsibilities would be more appropriate.

As indicated by the concept diagnosis-outcomes-interventions, selecting nursing intervention(s) is the third step in patient care planning.

As with NANDA-I nursing diagnoses and NOC outcomes, patients, caregivers, families and/communities are encouraged to participate in selection of NIC interventions as they are able, according to which interventions they think suite them best.

In the Careful Nursing semi-electronic care plans in use in Ireland NIC interventions are merged with evidence-based hospital nursing practice policies and guidelines for best practice, as indicated in the semi-electronic paper care plan shown in the summary section below.

The challenge of linking NANDA-I, NOC, and NIC SNL/Ts to create nursing care plans

The NANDA-I, NOC, and NIC SNL/Ts are each comprehensive and complex languages in themselves and can seem very challenging to use together to guide patient care plans, especially to begin with. But, once nurses become accustomed to using them most fairly quickly find them surprisingly easy to use.

In addition, guidance is at hand in a book which describes linkages between NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, NOC outcomes and NIC interventions (Johnson et al. 2012).

Links between NANDA-I diagnoses and NOC outcomes suggest relationships between patient problems and needs and their measured resolution as experience by patients. Links between NANDA-I diagnoses and NIC interventions suggest relationships between patient problems and needs and nursing activities that will help address problems or needs or resolve them. NOC and NIC work together to address patients problems or needs named as NANDA-I diagnoses.

The suggested links among the SNL/Ts described by Johnson et al. (2012) facilitate nurses understanding of how the languages/terminologies work together and help nurses to critically evaluate their patient care plans.

Summary

In Careful Nursing the NANDA-I nursing diagnosis, NOC and NIC SNL/Ts have a central role in planning nursing care. Some logistical problems can arise in implementing SNL/Ts, depending on the clinical setting and international location and some modifications may be required.

Nonetheless, these SNL/Ts keep us focused on nursing, provide us with a language to speak clearly and precisely about what we do and make it possible for us to measure, relatively easily, the outcomes of our practice. In effect, they give us greater authority over our practice.

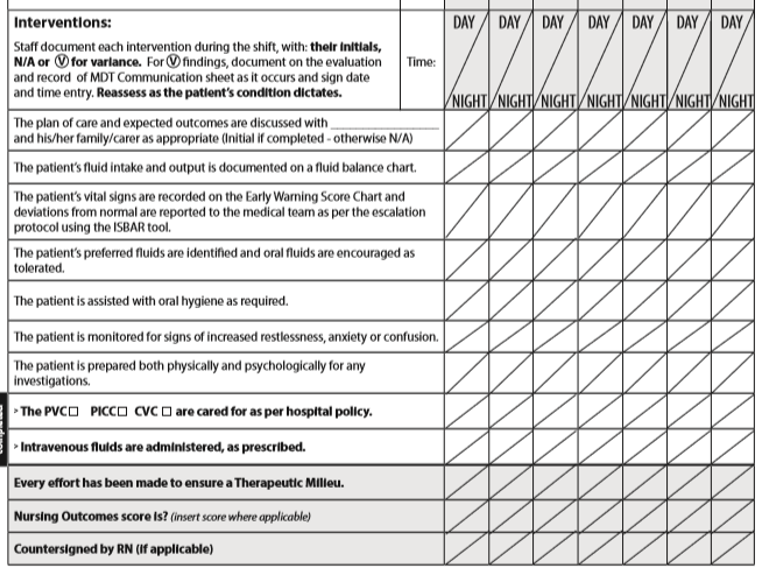

The following two Figures illustrate the current use of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, NOC and NIC in the semi-electronic paper care plans in Careful Nursing hospitals in Ireland, in this case for a patient with the NANDA-I diagnosis of Deficient Fluid Volume, the NOC outcome of Fluid Balance, and the nursing interventions being used in a particular hospital.

The first Figure below shows the top section of the care plan:

Notice the diagnosis and its definition at the top left. Notice the selected outcome and its measurement scale at the top right and the selected outcome indicators to the left below the diagnosis.

Below the selected outcome indicators is a space for the patient's outcome score on admission to the hospital or when the diagnosis is first made. This is followed by the outcome score that will be aimed for as a result of implementing the nursing interventions, followed by how often the outcome score will be measured, usually every 12 hours.

At the bottom the beginning of the interventions section is shown, which is continued in the second Figure below:

If an event occurs which deviates from the patient's expected responses it is considered a Variance and is reported in writing on a separate Variance page in the patient's chart. Frequent reassessment of patient's fluid balance condition is expected.

The first of the three shaded lines at the bottom of the page (which is included in all care plans) serves as an objective reminder to nurses to implement the Careful Nursing Therapeutic Milieu dimension to every extent possible.

The second shaded line requires nurses to enter the Fluid Balance outcome score every 12 hours.

The third line requires a countersignature by a professional nurse if the intervention has been performed by a nursing assistant or a nursing student.

These paper care plans have been constructed in this electronic format in preparation for implementation of national eHealth records. All care plans are works in progress and we are always working to develop and clarify them further.

Your diagnosis-outcomes-interventions self-rating:

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your ability to use defining characteristics, related factors, at risk factors and associated conditions to make a NANDA-I nursing diagnosis or check that an already selected diagnosis is the correct diagnosis?

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your ability to identify and consider differential NANDA-I nursing diagnoses for a given patient problem?

On a scale of 1 to 10,how do you rate your ability to select and measure appropriate NOC outcomes?

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your ability to select and use NIC interventions in your care planning, providing for an appropriate mix of NIC interventions and hospital evidence-based policies?

On a scale of 1 to 10, how do you rate your ability to engage patients/families/care-givers appropriately, and as they are able, in patient care planning?

On a scale of 1 to 10 how do you rate your ability to critically and constructively evaluate use of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, NOC outcomes and NIC interventions to guide nursing care planning?

Based on your assessment of your current skill in making NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, selecting appropriate NOC nursing outcomes and NIC nursing interventions (together with patients, family members, or care-givers where possible and appropriate), decide what you will do to further develop your skill in implementing this concept.

Make your own 'I will' statements . . .

Examples of diagnosis-outcomes-interventions 'I will' statements:

. . . work toward developing a thorough understanding of the NANDA-I nursing diagnoses commonly used to guide care for the types of patients I care for

. . . work toward developing a thorough understanding of the NANDA-I nursing diagnoses commonly used to guide care for the types of patients I care for

. . . discuss issues arising from use of NANDA-I, NOC and NIC guided care planning with nursing colleagues at least once a week

. . . explain and discuss my use of NANDA-I nursing diagnosis, NOC and NIC with other health professionals at least twice a month

. . . select a NANDA-I nursing diagnosis, NOC outcome or NIC intervention to take a

special interest in and contribute to its further development

References

Bulechek, G. M., Butcher, H. K., Dochterman, J. M., & Wagner, C. M. (Eds.). (2013). Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby.

Butcher, H. K., Bulechek, G. M., Dochterman, J. M. M., & Wagne, C. (Eds). (2018). Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (7th ed.). St. Louis, MI: Elsevier Inc.

Clarke, J. (2013). Spiritual Care in Everyday Nursing Practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Clarke, J. & Lang, N. (1992). Nursing's next advance: An internal classification for nursing practice. International Nursing Review, 39, 109-112.

Diagnosis (2019) https://www.etymonline.com/word/diagnosis

Fry, V.F. (1953) The creative approach to nursing. The American Journal of Nursing, 53, 301-302.

Gallagher-Lepak, S. (2018). Nursing diagnosis basics. In T. H. Herdman & S. Kamitsuru (Eds.), Nursing diagnoses definitions and classifications 2018–2020 (pp. 34–44). New York, NY: Thieme Publishers.

Gordon, M. (1982). Nursing Diagnosis: Process and Application. New York, NY, McGraw-Hill.

Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing Diagnoses Definitions and Classifications 2018–2020. New York, NY: Thieme Publishers.

Jarrin, O.F. (2010) Core elements of U.S. Nurse Practice Acts and Incorporation of nursing diagnosis language. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications (21) 166-176.

Jones, D. A. (2013). Nurse-patient relationship: Knowledge transforming practice at the bedside. In J. I. Erickson, D. A. Jones, & M. Ditomassi, (Eds.). Fostering Nurse-Led Care (pp. 85-121). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Jonhson, C.F. & Hales, L. W. (1989). Nursing diagnosis anyone? Do staff nurses use nursing diagnosis effectively? Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 20(1), 30-35.

Johnson, M., Moorhead, S., Bulechek, G.M., Butcher, H.K., Maas, M.L. & Swanson, E. (2012) NOC and NIC Linkages to NANDA-I and Clinical Conditions (3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Swanson, E. & Maas, M.L. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing outcomes classification (NOC): Measurement of Health Outcomes (NOC) (6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Maas, M. & Swanson, E. (Eds. (2013). Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC), (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Therese C. Meehan© July 2020