In Ireland, the turn of the 19th century bought with it the Acts of Union which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and tightened British rule of the country. These Acts did not bring with them the promised repeal of the infamous penal laws which denied the indigenous Irish their identity and basic civil liberties. Although these laws were being gradually eased, they still caused widely-felt discontent and set in motion the 29-year campaign for emancipation led by Daniel O'Connell (MacDonagh 1989). Living conditions were harsh with around 30% of people living in utter poverty and many more still very poor. These conditions, together with repeating occurrences of food shortages and infectious fevers lead to wide spread vulnerability, disability and sickness (Ó Gráda 1989). The need for health care and especially for skilled nursing was acute.

However, skilled nursing as a public service had been practically non-existent in Britain and Ireland for almost three hundred years following the Reformation and Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries which had provided medical and nursing services. Medicine had soon recovered but nursing had been neglected leading to 'the darkest known period' in its history (Nutting & Dock 1907/2000, p.499).

With easing of the penal laws it became possible by the 1820s for Irish women concerned with the plight of the sick poor to act on their desire to care for them. Social circumstances required that they form organisations of religious sisters, Sisters of Mercy led by Catherine McAuley and Irish Sisters of Charity led by Mary Aikenhead.

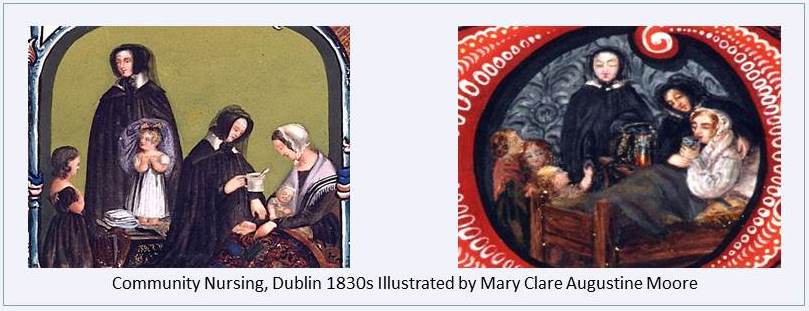

Beginning in Dublin, the sisters went out daily to care for the sick poor in their homes, providing physical, spiritual and emotional comfort and consolation, as well as advice about coping with diseases and social conditions (Atkinson 1879, Carroll 1883).

They became known affectionately as 'the walking nuns'. Daniel O'Connell, quoted in a letter from McAuley to Leahy (13 November 1840), particularly expressed admiration for them:

Look at the Sisters of Mercy, wrapped in coarse black cloaks–hear, hear–they are seen gliding along, persons apparently poor–while a slight glance at the foot shews the educated Lady. They are hastening to the loan couch of some sick fellow creature fast sinking into the grave with none to console, none to soothe [sic]. . . .–oh such is too good to be oppressed. Great cheering.

In 1832, during the first great cholera epidemic of the 19th century, furious public pressure lead to the sisters being 'invited' to provide nursing care at Dublin cholera hospitals. The Sisters of Charity served for three months at the Grangegorman hospital (Atkinson 1879) and the Sisters of Mercy for seven months at the Townsend Street Depot hospital (Carroll 1883). This was possibly the first time since Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries that religious sisters were permitted officially to practice nursing in public hospitals in Britain and Ireland.

They cared for patients daily, four at a time in four-hour shifts, from 9:00 a.m. often until 8:00 p.m. They went from bed to bed, mostly on their knees as beds were low to the floor, keeping patients as clean and comfortable as possible, administering food, fluids and palliatives and giving all possible spiritual and emotional consolation. The head doctor gave Catherine McAuley the 'fullest control' of patient care and 'held long consultations with her' (Carroll 1883, p.295). One of her fellow-nurses, Mary Clare Moore, wrote that she 'scarcely left the hospital' (quoted in Sullivan 1966, p.15). She, along with her companion-nurses, supervised the care of patients and the work of lay nurses, and Catherine took full responsibility for the dying and the dead (Carroll 1866). A doctor who worked with them later said that 'they were of the greatest use' and that 'the hospital could not be carried on without them. They kept eighty lay nurses in order, which was hard to do' (Carroll 1883, p.295).

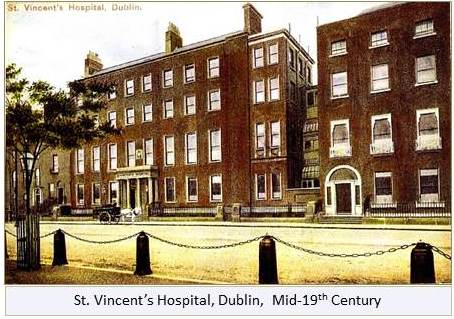

In 1833, three Sisters of Charity went to hospitals in Paris for a year of specialised nursing training and in 1835 Mary Aikenhead founded St. Vincent's hospital in Dublin, possibly the first major public hospital to be owned and operated by nurses in Britain and Ireland in modern times.

As Daniel O'Connell observed, many of these nursing sisters were well educated women. Catherine McAuley was an avid reader and had close family connections to the medical profession. During the cholera epidemic they gained valuable experience in nursing and hospital management under critical conditions, working closely with doctors, apothecaries, and lay nurses. Afterwards they continued and expanded their community nursing, and during times of crisis were permitted to serve in workhouse hospitals. In effect, over these years they reformulated skilled nursing as a public service and developed what at the time was called a nursing system. It was a distinctively Irish nursing system because it was framed by Irish culture with its long history of deeply-rooted spirituality, concern for the care of the sick and injured and attentiveness to the common good.

Early historians Nutting and Dock (1907/2000) recognised their achievement; that they 'early attained brilliant prestige in nursing', and observed that they 'must have had hospital training at an early date, for they had skilled nurses when the Crimean war broke out' (p.86).

It is of note that Mary Clare Moore who, practically speaking, received her 'nursing training' from Catherine McAuley over their seven months working together at the Townsend Street Depot cholera hospital, was to pass on her nursing knowledge and experience to Florence Nightingale twenty-two years later during their seventeen months working together at the Scutari Barrack hospital during the Crimean war.

References

Atkinson S [S.A.] (1879) Mary Aikenhead: Her Life, Her Work, and Her Friends. MH Gill & Son, Dublin.

[Carroll MA] A Member of the Order of Mercy (1866) Life of Catherine McAuley. D&J Saddler & Co., New York.

[Carroll MA] A Member of the Order of Mercy (ed) (1883) Leaves from the Annals of the Sisters of Mercy, (vol 2). Catholic Publication Society, New York.

MacDonagh O (1989) Ireland and the union, 1801-1870. In A New History of Ireland Vol. V, Ed. W. E. Vaughan. Oxford University Press. Pp. vii-xv.

McAuley C (1840) [Letter from Catherine McAuley to Mary Catherine Leahy, November 13th]. Archives of the Convent of Mercy, Galway, Ireland.

Nutting A & Dock L (1907/2000) A History of Nursing From the Earliest Times, to the Present Day With Special Reference to the Work of the Past Thirty Years. Vol.3 Bristol, UK, Thoemmes Press.

Ó Gráda C (1989) Poverty, population and agriculture, 1801-1845. In A New History of Ireland Vol. V, Ed. W. E. Vaughan. Oxford University Press. pp. 108-157.

Sullivan M (1996) Catherine McAuley and the care of the sick. The Mast 6(2), 11-22.

Illustration Credits

Likeness of Catherine McAuley. Courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy, Dublin, Ireland

Photo of Mary Aikenhead as a young woman. Courtesy of the Religious Sisters of Charity, Dublin, Ireland.

Illustrations of community nursing, Dublin, 1830s by Mary Clare Augustine Moore. Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Mercy, Dublin, Ireland.

Illustration of St. Vincent's Hospital Dublin in the mid-19th century. Courtesy of the Religious Sisters of Charity, Dublin, Ireland.

Therese C. Meehan © March 2020