Blog

Edith Stein: A philosopher for nursing

Who better to help guide us in our practice than a phenomenological philosopher who offers us a theory of empathy, a theory of values, and a theory of how human persons relate to one another in community?

If you don't already know her, let me introduce you to Edith Stein.

Edith was born in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland) in 1891, the 11th and youngest child of a devout Jewish family. She recounts her lively, happy childhood in her autobiography, Life in a Jewish family, 1891-1916. Her family early noted her vibrant intellect and she excelled at school. In her early teens, to the dismay of her family, she gradually abandoned her Jewish faith and by the age of 21 described herself as an atheist.

When she began her studies at the University of Breslau in 1911 she wanted to study the new discipline of psychology. But instead she became fascinated with phenomenology and the work of Edmund Husserl. In 1913 she transferred to the University of Göttingen to study with Husserl and became a member of a close circle of his students.

As a student with Husserl, Edith was faced with writing a doctoral thesis and began to search for a topic. She became interested in the idea of empathy (Einfühlung) which Husserl had adopted, that is, the experience by which human beings have access to the experience of other human beings. She observed that although Husserl talked about empathy, he had not actually defined it. Thus with Husserl's approval, she had her topic: What is empathy?

But when war broke out in 1914 all studies were suspended. Edith registered immediately for a nursing course in Breslau. As a Red Cross nurse was assigned to the lazaretto (infectious diseases) section of a 4,000 bed military hospital in Austria. Here she worked for most of 1915. In her autobiography, noted above (pp.320-365), she describes in detail her experiences nursing wounded soldiers suffering from diseases such as typhoid, cholera, typhus, dysentery and a range of other conditions such as frostbite and pneumonia.

But when war broke out in 1914 all studies were suspended. Edith registered immediately for a nursing course in Breslau. As a Red Cross nurse was assigned to the lazaretto (infectious diseases) section of a 4,000 bed military hospital in Austria. Here she worked for most of 1915. In her autobiography, noted above (pp.320-365), she describes in detail her experiences nursing wounded soldiers suffering from diseases such as typhoid, cholera, typhus, dysentery and a range of other conditions such as frostbite and pneumonia.

It is easy to imagine Edith continuing to think about her dissertation topic as she cared for the sick soldiers, many of whom were critically ill and dying; of her being very aware of how she experienced their feelings and how she responded to their feelings; of her thinking about how her patients were aware of and responded to her presence, feelings and judgements.

.jpg)

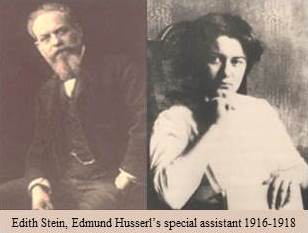

In early 1916 the need for nurses declined and Edith returned to her phenomenological study with Husserl, now Professor at the University of Freiberg. She completed her doctoral thesis and defended it with honours in August 1916. It was later translated into English and is available to us today as On the Problem of Empathy.

For two years Edith continued to work very closely with Husserl as his special assistant, helping him develop his ideas and clarifying and organising his notes and lecturers. It is widely recognised that she contributed significantly to his work.

During this time, as part of her application for a permanent university position, Edith wrote three further theses on the nature of human persons and their relationships in community. These encompass her value theory and theory of how persons live in community. They have been translated into English and are available to us today as Philosophy and Psychology of the Humanities.

For his part, Edmund Husserl showed himself to be a man of his time. He was not prepared to support Edith in her application for a permanent academic position – because he believed that women did not belong in the realm of academia.

Edith obtained a teaching position at a girls' high school. In addition, she became a popular speaker, well known as an educator and a feminist.

During the time Edith worked with Husserl and wrote On the Problem of Empathy and Philosophy and Psychology of the Humanities, she remained an atheist. But it is interesting to notice that in Philosophy and Psychology of the Humanities she views the human being as a human person who is unitary in nature and has a spiritual dimension.

As time passed Edith gradually developed a deep spiritual life. In 1922 became a Catholic and in 1934 she entered a Carmelite Monastery in Cologne; there the nuns asked her to continue her philosophical writing. In 1938, as the dark clouds of Nazism gathered over Germany, Edith was moved to the Netherlands for her safety. But in August 1942, after the Netherlands was occupied, Edith was arrested and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp where she died in the gas chamber. Edith continued to write as a philosopher up until the time she was arrested.

Edith Stein's legacy to nursing

Two of Edith Stein's books mentioned above, On the Problem of Empathy and Philosophy and Psychology of the Humanities, are of immense importance for the nursing profession.

On the Problem of Empathy contributes significantly to the development of knowledge about human relationships; for nursing, the all-important nurse-patient relationship. It explains our lived experience of nursing practice, especially how we can be truly present to patients, and have deep compassion for patients who are suffering without being overwhelmed by their, pain, distress and anguish.

Philosophy and Psychology of the Humanities contributes significantly to knowledge about what values are and how they motivate human behaviour. For nursing, it offers us a way to understand how our professional and personal values motivate our practice attitudes and activities. It also offers us insight about what happens when we fail to honour our professional values and how this problem can be overcome.

We will gradually merge Edith's phenomenological philosophy into the philosophical foundation of the Careful Nursing Philosophy and Professional Practice Model. This will be a natural development because Edith's philosophical writings are consistent with the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas.

In beginning to explore Edith Stein's legacy we have a problem to overcome

In an odd kind of way Edith's philosophy can be very difficult to read and get the hang of. For example, you start reading On the Problem of Empathy, a topic so close to our professional heart, and you find it hard to follow; hard to stay with. One or two pages later you put it aside, thinking you'll try again later. The odd thing is that it's actually not hard to read; it just seems as though it is.

Help is at hand

Our help is in the form of a recently published book which explains Edith's ideas in a more easily understandable way. It is called The Philosophy of Edith Stein and is written by Dr. Mette Lebech, who is based in the Department of Philosophy at Maynooth University. Mette has specialised in the philosophy of Edith Stein over a number of years.

In this book Mette introduces and explains to us the development of phenomenology and of Edith as a phenomenological philosopher. She opens up for us Edith's philosophy of who we and our patients are as human persons and our potential as human persons in community.

In this book Mette introduces and explains to us the development of phenomenology and of Edith as a phenomenological philosopher. She opens up for us Edith's philosophy of who we and our patients are as human persons and our potential as human persons in community.

Mette also includes a chapter on Edith's philosophy and theories of education and on her feminist perspective on the role of women in society.

But, perhaps for nurses the best place to begin this book is with the last chapter: "A Steinian approach to dementia". Here Mette helps us understand how Edith's philosophy can help us gain insight into the lived experience of persons suffering from dementia.

If you do nothing else, read this chapter.

Welcome to the world of Edith Stein !

Therese Meehan