In a nutshell . . . .

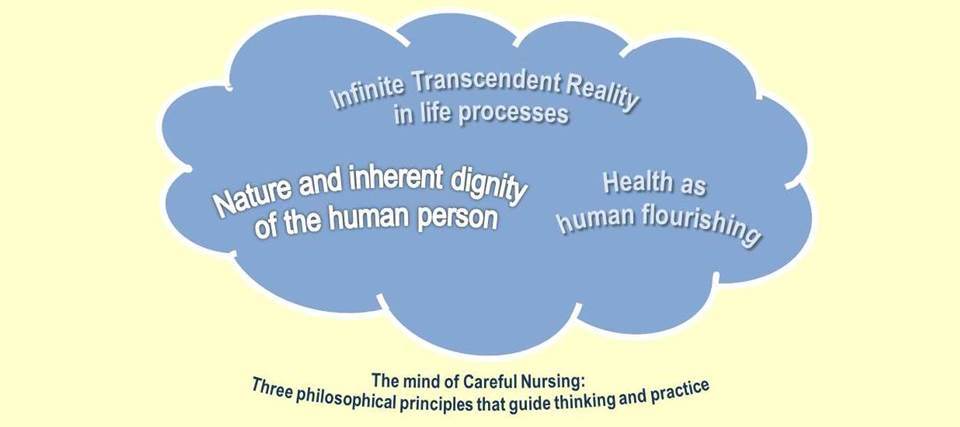

You'll see in the following illustration that this principle is the first of three principles that together make up the mindset of Careful Nursing. Human beings are defined as human persons. You'll read about what it means to be a human person based on the original meaning of the word, person, and development of this meaning over time.

Key qualities that define a human person are discussed. Human persons are in essence unitary (holistic), spiritual beings who possess a distinctive capacity to reason; they possess intellectual and loving being, and in-built and unconditional dignity and worth, qualities which they can never lose or have taken from them. Nurse-patient relationships are human person-human person relationships.

The Careful Nursing philosophy of the human person is shown to explain the true nature of holism in nursing, and an example is given of what this means in nursing practice.

Other meanings of the term person are identified. Recognised lack of clarity about the meaning of person and person-centred care in nursing and healthcare generally is identified.

What we think is true about human beings is of vital importance in any approach to nursing practice because nursing is in a special way a deeply human practice. This is most evident in the widely-held importance of the nurse-patient relationship. Professional nursing is in its most fundamental sense a nourishing practice; one human being, a nurse, nourishing another, a human being who is sick, injured or vulnerable; hence the name nurse (Partridge 1958). In Careful Nursing, drawing on a long intellectual tradition adopted in the philosophy of Aquinas, human beings are defined as persons.

The human being as a human person

The terms human being and human person are commonly used interchangeably but they do not have the same meaning. Further, in contemporary society the word person has a range of different meanings, some of which are mentioned at the end of this page. In Careful Nursing we use the definition of human person which was adopted and elaborated by Aquinas because it addresses comprehensively the complex nature of human life and human relationships in a way that is consistent with nursing.

Development of the meaning of person

Use of the word person evolved over several centuries in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. Originally person (prosopon or persona) meant a mask or "something added to one's being, or it referred to the eyes" (Clark 1992, p.11). Gradually the meaning of person evolved as a metaphysical concept. By the 4th century the term "person is a rational substance" appeared in Latin documents (Hadot, quoted in Clark, p. 11), and person became associated with the spiritual dimension of human life. Person came to refer to the deeply relational aspect of human life and human persons were understood as "distinct possessors of intellectual and loving being" (Clark 1992, p.12).

In the 6th century, the Roman statesman and philosopher, Boethius (519/1918), building mainly on ideas of Plato and Aristotle, formulated a widely influential definition of the human person as: "The individual substance of a rational nature"' (p.85). This is a metaphysical definition of the essential nature of the human being as a person.

This definition was adopted and elaborated by Aquinas (1265-1274/2007, Pt. I, Q. 29, Art. 1; Q. 75-102)* and continues to be relevant today (Simpson 1988). This definition is used by modern and contemporary philosophers who base their thinking on the philosophy of Aquinas, for example, Jacques Maritain (1966), Mary Clark (2000), Alasdair MacIntyre (2007) and associated philosophers, for example, the phenomenological philosophers Edith Stein (1921/1989, 1922/2000), and Mette Lebech (2009).

It is important to keep in mind that this metaphysical definition of a human person, composed of abstract concepts, is applied analogically in our everyday understanding of persons in practice; that is, the metaphysical definition is used to help us apply understanding of the nature of persons, ourselves and the people we care for, in the concrete world of our practice.

Aquinas's understanding of person is used to give an account of what it means to be a person from a Careful Nursing perspective. We use this definition because it helps explain concepts and experiences central to nursing practice, for example, holism, inherent human dignity and person-centred care.

As nurses, our attentiveness to sick, injured and vulnerable people brings us to engage closely and often deeply with the mysterious reality of human life in our patients, ourselves, and others who we work with. Sarter (1988) observes that the deeply human nature of nursing practice brings us "into daily encounters with the heights and depths of human experience" and requires us as individual nurses and as a professional group to seek answers to metaphysical questions which concern nursing practice (p.187).

Commenting on the importance for nursing of having a clear understanding of the human person, Green (2009) observes that "Because nursing is an activity carried out by persons with other persons, no nursing theory can give an account of itself without giving something of an account of what it means to be a person" (p. 265).

Aquinas's metaphysical definition of a human person is complex but every effort is made here to state it in a clear and uncomplicated way. This account is based on Aquinas as referenced above and literature which discusses Aquinas's definition and explanation of the human person, mainly Clark (1992, 2000).

It must be noted that although Aquinas has a special and deep interest in the spiritual dimension of the human person, he consistently applies his ideas to our every-day experience of the world. Aquinas has a special and detailed interest in human emotions and the bio-physiology of the human body and senses. He recognises the vital importance of our emotions it how we act and he reasons that because we live our lives through our body, our knowledge of and use of our body is of immense importance.

The nature and inherent dignity of the human personProposition: a person is "The individual substance of a rational nature".

What is a substance?

We usually think of a substance as material matter but here it is used in its metaphysical meaning to describe the essence of things, here the essence of human beings as persons. The substance, or essence, of human persons is a spirit/body composite or fusion which exists independently in itself. Each person is a distinct being, undivided in itself.

The spirit component is the non-material form of the person and comes into existence only in union with the body of the person, guiding the organisation and actions of the body. The spirit is intimately associated with the mind of the person which knows through the being of the person. Persons can know their spirit only through their intellect.

As the spirit permeates the body with which it is unified it animates its vital operations. Human persons' experience of reality, self-communication, and expression of thoughts, desires, feelings and decisions are made possible through their body. Persons express themselves through bodily attitudes and actions; through 'bodiliness'. Persons' attitudes and activities can be understood only within the context of the unitary spirit/body composite.

Key point: human persons are, in their essence and experience of being, unitary beings (what we commonly call holistic).

The spiritual component of persons receives being from an infinite, absolute, most perfect pure spiritual being, which is the source, or 'first mover', of all created things. In Careful Nursing this pure spiritual being is called Infinite Transcendent Reality in life processes, reflecting that human persons possess spiritual being (this will be discussed in the second philosophical principle, Infinite Transcendent Reality in life processes).

Key point: human persons have a spiritual dimension.

Human persons, in their reception and possession of being from the absolute and most perfect pure spiritual being, live in participatory relationship with this pure spiritual being; to some extent they consciously experiences this relationship, in as much as they seek to do so. Similarly, participatory relationship is experienced deeply within and among human persons, especially in terms of fundamental needs, feelings and desires that are essential to survival, well-being and flourishing.

Key point: that human persons are in essence deeply relational beings.

What does individual substance mean?

Each human person in their substance/essence is an individual existing independently in itself. But, the meaning of individual substance is used here to qualify substance. That is, individual refers to the individual distinctiveness among human persons. Each individual human person has distinctive characteristics and is engaged in unique acts of existence; each is recognised as an individually unique human person.

Key point: human persons are each distinctive and unique.

What does it mean to have a rational nature?

Here the term rational nature refers to the distinctive human characteristic of intellectual being; of human beings' highly developed capacity to know through reasoning. As noted above under Substance, the spirit of persons is intimately associated with the person's mind. In fact, for human persons their spirit is viewed as the wellspring of their intellectual activity; of their thinking, reasoning and knowing.

Thus for human persons their spirit, as well as being spiritual, is understood to be intimately fused with their highly developed reason/intellectual being, in what could be thought of as a spirit/mind unity. This spirit/mind unity or intellectual being of a person draws on and processes the massive range of information it continuously receives from the five outer senses through the body's nervous system. As noted above under Substance, persons' experiences, attitudes and activities are made possible through their body's sensory system.

As the same time persons, while their spirit/mind unity or intellectual being is highly dependent on their sensory awareness mediated through their body's nervous system, their intellectual being encompasses their capacity to know also in a way that transcends their sensory awareness. This appears evident, for example, in conceptualising, imagining, reflecting, valuing, loving and choosing freely, activities emerging from knowledge which appears to not depend entirely on the body's sensory system.

Key point: human persons possess intellectual being and a highly developed capacity to reason. Intellectual activity informed by sensory experience also has the capacity for knowing that transcends sensory experience.

Aquinas adds to his understanding of the person two additional arguments. Intimations to and versions of these arguments appear in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and literature over many centuries prior to Aquinas.

Proposition: Human persons distinctively possesses intellectual and loving being

A central aspect of Aquinas's use of Boethius's definition of the human person is his emphasis on the spirit in the spirit/body composite that forms the essence of the person. Aquinas focuses on persons' being which they possess as they have received it from the absolute and most perfect pure spiritual being. Aquinas argues that absolute spiritual being is an intrinsically and abundantly loving being which creates and sustains all human beings through loving participatory relationship with them as unitary human persons.

Thus, through participatory relationship with absolute spiritual being, human persons are imprinted with free will and a fundamental capacity to express generosity of spirit, kindness and compassion which they can know and develop through their intellectual being. Thus, as well as sustaining and developing their relationship with absolute spiritual being, human persons are empowered and predisposed to express generosity of spirit, kindness and compassion in relationship with one another; to be unconditionally "creative of others by actions that are loving and promotive" Clark 1992, p. 12).

Key point: human persons are predisposed to express unconditional generosity of spirit, kindness and compassion in relationships with one another and, thereby, foster human health, well-being and flourishing.

Proposition: All persons possess inherent dignity and worth

Aquinas argues that all human beings have spiritual being. Therefore, all human beings are considered to be persons. When understood as persons, all human beings have inherent dignity and worth arising from their partly spiritual nature and metaphysical likeness to the infinite, absolute, most perfect pure spiritual being. Thus, all human beings/persons are understood to have unconditional inherent value and worth which they can never loose. Although human persons are individually distinctive and each is unique, all share equally in inherent human dignity. Human dignity is the highest human value and because all persons are equal in this highest human value it is a unifying value (Lebech 2009).

Key point: all human persons, unconditionally, have inherent dignity and are of the greatest worth, qualities which they can never lose or have taken from them.

The above key points are summarised in this Table:

Whole persons as unitary beings

Our practice is guided by our understanding of ourselves and the people we care as unitary human persons. This is easier said than done; as a result most nurses use the term holistic for unitary – but holistic usually does not mean unitary.

The word holistic as it was coined in the 1920s by Jan Smuts, a South African statesman and army commander, meant unitary. In fact, in the second edition of his book Holism and Evolution published in 1927 Smuts notes that his idea of holism has a "strikingly similarity" to the thinking of Aquinas (p.106). Smuts had discovered that the unitary nature of human persons, what he termed holism) had been widely examined and discussed by philosophers for centuries.

The unitary/holistic dilemma

Using the word holistic in nursing confronts us with a dilemma because it has largely lost its original meaning of a unitary being. Instead, in nursing it has mostly come to mean the whole person as an addition of discrete parts that we can perceive with our five senses (Stiles 2011).

The reason for our dilemma is that when we understand a person as a unitary whole, what we see as particular parts of the person 'disappear' from our view or we become unable to attend to them. This is a seemingly impossible problem for nursing because we are focused continually on caring for parts of people, for example when dressing a wound, monitoring a blood transfusion, assessing vital signs or providing mouth care.

Understanding the idea of holism as an addition of discrete parts is a workable solution for other health professions but is not workable for nursing. Why? The reason why is that nursing care for people takes place in an especially distinctive way within the context of nurse-patient relationships – and nurse-patient relationships are holistic.

We know from experience that nurse-patient relationships are holistic/unitary. We and the people we care for cannot perceive with our five outward senses our relationships with one another. The relationships themselves are invisible. But when we do not consciously attend to people we care for with kindess and generosity of spirit, they can feel deeply hurt by their perceived lack of our nurturing relationship with them. Patients may describe this perceived lack of relationship as 'the nurse wasn't really here'. This can be deeply distressing to anxious or fearful patients.

Answer to the unitary/holism dilemma

Because this unitary/holistic-as-parts dilemma is particular to the nursing profession, we must find a way to solve it. How can we simultaneously perceive ourselves and the people we care for as holistic/unitary beings and at the same time attend to their parts?

Aquinas offers Careful Nursing a subtle but practical answer to this question. He argues that while human persons are in essence holistic/unitary beings, they have two distinguishable realities; a bio-physical reality of body and senses – a visible outward life – and a psycho-spiritual reality of mind and spirit – and invisible inward life. These realities are not parts of persons but are realities which can be distinguished within the unitary whole (Aquinas 1265–1274/2007, I Q75, Art. 4; Q76; II Q23, Art.1).

Thus, according to Aquinas all human beings lead a two-fold life, an outward life of body and senses and an inward life of mind and spirit. We know our outward life of body and senses using our five senses. But we can only know our inward life of mind and spirit by using our inward mind's eye of our intellect. Our inward life of mind and spirit is 'visible' to us only in our mind.

The following three illustrations show this idea and its reality in our nursing practice and management.

They show the reality of our outward visible life of body and senses which we all know very well.

They also show the reality of our inward invisible life of mind and spirit which we don't usually know as well. We are not accoustomed to recognising our natural ability to know our inward life using our mind's eye of our intellect.

Keep in mind that in holistic/unitary nursing care of people bio-physical care of body and senses and psycho-spiritual care of mind and spirit happen simultaneously; they are part of one another.

Consider this first example of a nurse in an ICU caring for an unconscious patient.

Consider this second example of a nurse in an out-patient clinic helping a patient plan for the first time how to organise and take tablet medications he is starting on.

Consider this third example of two nurses in a hospital in-patient clinic administering and monitoring a blood transfusion for a hospitalised patient.

Nurse-patient relationships

We know from our philosophy that as human persons, we and the people we care for are deeply relational beings. We know that participatory human relationships are essential to human survival, well-being and flourishing. The sick, injured and vulnerable people we care for experience particularly the importance of participatory human relationships as they engage in their healing process and aim for restoration of health. Nursing practice, as essentially a professional nurturing practice, responds distinctively to this essential human need.

The long and widely held emphasis in nursing on the importance of the nurse-patient relationship attests to this understanding. Certainly all health professions are committed to engage in healing relationships with patients. But the protective, nurturing responsibility of nurses and the profession's relational continuity with patients is a distinctive and special characteristic and therapeutic quality of the nursing profession.

The long and widely held emphasis in nursing on the importance of the nurse-patient relationship attests to this understanding. Certainly all health professions are committed to engage in healing relationships with patients. But the protective, nurturing responsibility of nurses and the profession's relational continuity with patients is a distinctive and special characteristic and therapeutic quality of the nursing profession.

A spiritual relational component: We also know from our philosophy that as human persons we and the people we care for are unitary spirt/body beings and that spiritual being underpins relational being. We assume that this spiritual characteristic is experienced in the usually unspoken unitary being and inward life of mind and spirit. This is an aspect of ourselves that we all experience in our own individual ways, whether or not we think of this experience as spiritual. Our deeply relational spiritual being can be experienced as part of our professional relationships with patients as we attend to, protect and support them in their healing process.

Whether we are greeting a patient, administering medications, or carrying out technical procedures, we are doing so within the context of the nurse-patient relationship; a person-to-person relationship. It is widely recognized that the quality of these relationships can have a significant influence on the effectiveness of our practice.

An intellectual relational component: We also know from our philosophy that we and the people we care for possess a highly specialised intellectual nature which is linked to our spiritual being. We and the people we care for each "have the capacity to direct [our]selves freely, by [our] will, toward the end that [each has] apprehended by their mind' (Emery 2011, p. 996). Following Aquinas, Emery emphasises that this spiritual intellectual nature exists in all human persons "including severely handicapped people who will perhaps never be able to think or to form projects" (p. 996).

In our practice we are continuously watching and assessing the people we care for both formally and informally and recognising what we see or perceive. Our reasoning is objective and scientific but in our relationships with patients it is also open to our "capacity to be aware of or to know whatever there is to be aware of or to be known, and to order actions, traits of character, emotions accordingly" (Simpson, 1988, p. 215). Our reasoning is also open to sudden insights; to reason's intuitive grasps (Maritain 1952); of patients' condition or experience of illness, vulnerability or healing.

Our relational predisposition: The spiritual, intellectual relational components of our practice predispose us to unconditionally relate to the people we care for with generosity of spirit, kindness and compassion. This predisposition is reflected in how we engage in nurse-patient relationships; always with attentiveness to who patients are as persons, even when circumstances are very stressful and rushed.

Human dignity

As human persons, respect for human dignity and the goodness and worth of all human beings is a fundamental aspect of our practice. As persons, we are unconditionally oriented to respecting the inherent dignity and worth of every patient, colleague, care assistant, and all persons. In addition, as all persons are distinctive and unique we are likewise oriented to recognising and respecting individual dignities of identity.

The unifying characteristic of inherent dignity means that despite our individuality and diversity we are unified in this highest human value (Lebech 2009). As human persons we share this value, have the capacity to respect it in one another equally and unconditionally, and use it to support one another and the people we care for.

Summary

This overview of how human persons are defined and understood in Careful Nursing has presented a basic understanding of human persons for Careful Nursing practice. It draws on the original meaning of human person as it was interpreted and developed by Aquinas. Aquinas's philosophy of the person has its roots in the earliest philosophical thinking in the Western world about the nature and meaning of being a human person. Aquinas's philosophy of the person is found relevant by modern and contemporary scholars.

The original meaning of human person which we use in Careful Nursing is complex and cannot be fully understood in one reading. Understanding comes from re-reading, re-thinking, reflection, analysis and critical evaluation over time. Understanding also comes from reflection on the experience of using this definition of human persons in practice, on testing our understanding in participatory relationship with the people we care for, and reflecting on the nursing profession's distinctive role in protecting patients from harm and fostering human healing, or a peaceful end of life.

Postscript: Person has many different meanings

In considering the meaning of the human person in Careful Nursing, it is important to consider the wide variation of meaning currently given to the term person in nursing and in health care at-large.

Contemporary meanings of person range from technical to transcendent. Dictionary definitions of person include a human being regarded as an individual, an individual's body, or the inner character or personality of an individual; in law a person is a human being or legal entity such as a company which has legal rights and obligations (Person 2017).

Philosophical meanings of person include those of Karl Rahner and Emmanuel Levinas. Rahner views persons as unitary individuals consisting of spirit and matter who are self-consciously and lovingly oriented to the mystery of spiritual being in relationship with others (Brett 2013). Levinas describes persons in terms of how individual human beings encounter one another. Levinas proposes that persons encounter one another face-to-face in transcendent interpersonal relationship and recognise their ethical responsibility to act in relationship for the good of the other (Beavers 1990). In humanistic psychology Carl Rogers (1989) uses person to mean an individual who has a transpersonal tendency to strive for self-actualisation in a self-directed process of achieving personal goals, wishes, and desires in life.

Concern about meanings of person and person-centred used in nursing and healthcare

The word person is increasingly used in healthcare mainly in relation to the idea of person-centred care, but rarely is a definition of person provided. The term person-centred has almost become something of a buzz-word. Person-centred care can be simply a substitute for the term patient-centred care. It is often used to indicate that patients are invited to guide the care they receive in the sense of the dictionary definition 'to be one's own person', 'to do or be what one wishes or in accordance with one's own character rather than as influenced by others' (Person 2017).

At the same time, person-centred is usually used with deep respect for patients, for example, Kogan et al. (2016) propose that when patients are regarded as persons they are recognised as having the capacity to deliberate freely on their healthcare needs, preferences and personal values and, themselves. Patients are viewed as having a central role in guiding their healing process with the support of holistically oriented, empathetic healthcare providers.

McCance et al. (2011) recognise person-centred care as a complex process which is underpinned by values and focuses on nurses' holistic, sympathetic, skiful and respectful presence and interpersonal engagement with patients and with colleagues, and patient-guided shared decision-making. These authors have extended their understanding of person-centred care to encompass all health care providers and people cared for in a given health system who together foster a healing culture and healthful relationships (McCormack & McCance 2017).

Dewing and McCormack (2016) have pointed out the wide-spread lack of clarity about the meaning of person-centredness and observe that the concept continues to undergo development. They suggest that the meaning of person-centredness will be socially constructed and developed within a scientific context.

The view that person-centredness should be at the centre of healthcare is very important. To-date most discussion of person-centred care focuses on how people act to engage in and direct healing and health. But little attention appears to have been given to the philosophical meaning of the term person and its implications for what it means to be and act as a human person.

Careful Nursing uses the philosopy of Aquinas as the guide to the meaning of the term human person; on who human beings are as persons; on what it means to be a person. Person-centred care in Careful Nursing means using the assumptions outlined in the Table above as a basis for caring for sick, injured and vulnerable people and in all human interactions concerned with that care.

* The standard method of referencing specific sections of Aquinas's Summa Theologica is according to Parts (P), Questions (Q), and Articles (Art).

References

Aquinas T (1265-1274/2007) Summa Theologiae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Beavers, A. F. (1990). Introducing Levinas to undergraduate philosophers. Colloquy paper, Undergraduate Philosophy Association, University of Texas. Austin.

Boethius, A. M. S. (circa 519/1918). The theological tractates (H. F. Stewart & E. K. Rand trans.). William Heinemann. London..

Brett GJ. (2013). The Theological Notion of the Human Person: A Conversation Between the Theology of Karl Rahner and the Philosophy of John Macmurray. Peter Lang. Oxford.

Clark, M. T. (1992). An inquiry into personhood. Review of Metaphysics,46, 3-28.

Dewing J & McCormack B. (2016) Tell me, how do you define person-centredness? (Editorial) Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 2509-2510.

Emery, G. (2011) The dignity of being a substance: person, subsistence, and nature. Nova et Vetera (English Edition) 9, 991-1001.

Green C. (2000) A comprehensive theory of the human person from philosophy and nursing. Nursing Philosophy, 10, 263–274.

Kogan AC, Wilber K & Mosqueda L. (2016) Person-centered care for older adults with chronic conditions and functional impairment: A systematic literature review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64 (1), e1-e7.

Lebech, M. (2009). On the Problem of Human Dignity. Verlag Konigshausen & Newmann, Wurzburg.

Partridge, E. (1958). Origins. The Macmillan Company, New York.

Person (2017) Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/person

Macintyre A. (2007) After Virtue, (3rd ed.) University of Notre Dame Press. Notre Dame IN.

Maritain, J. (1952). The Range of Reason. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

Maritain, J. (1953). Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry. Pantheon Books New York.

McCance T, McCormack B. & Dewing (2011) An Exploration of Person-Centredness in Practice. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 16 (2).

McCance T & McCormack B (2016) The person-centred practice framework. In McCormack B. & McCance T eds. Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice (2nd ed. Wiley Blackwell, Oxford.

Rogers, C. (1989). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Mariner Books: Houghton Mifflin, New York, NY.

Sarter, B. (1988). Metaphysical analysis. In B. Sarter (Ed.), Paths to knowledge: innovative research methods for nursing (pp. 183-191). National League for Nursing. New York.

Simpson, P. (1988). The definition of the person: Boethius revisited. New Scholasticism, 62, 210-220.

Smuts, J. C. (1927) Holism and evolution. Macmillan & Company, London.

Stiles K (2011) Advancing nursing knowledge through complex holism. Advances in Nursing Science, 34, 39–50.

Therese C. Meehan© September 2017 / updated July 2022